On February 1, 2013, Hiroshima University established two new programs: the “Distinguished Professors” (DP) program and the “Distinguished Researchers” (DR) program. Individuals who are part of these programs are recognized as senior and junior faculty members respectively, who are engaged in extraordinarily distinguished research activities.

EXCITEMENT IN A BLACK BOX

“The brain used to be a black box. You cannot approach the brain directly, like you can simply biopsy a tumor to study cancer.”

Distinguished Professor Shigeto Yamawaki has opened up that black box over the course of his 27-year career at Hiroshima University, making important strides in advancing medical understanding of the human brain.

Yamawaki leads a research project called “Center of KANSEI Innovation: Nurturing Mental Welfare”, working in collaboration with a Japanese car company and many other research institutes and manufacturing companies. The project team’s ultimate goal is to create a happy society that nurtures mental welfare, where objects function in harmony with people’s minds. The immediate goal of the project is to develop Brain Emotion Interfaces using optics, information, and communications technologies in combination with neuroscience to establish inter-person and object-person connections through KANSEI, a Japanese word which Yamawaki says does not have a direct English translation.

“To explain KANSEI, usually we say feeling, or mood, or emotion, sensibility… but the idea is actually higher… it includes greater meaning… it is very Japanese,” he says, trying to explain.

Part of Yamawaki’s work involves studying positive moods like happiness and excitement. The research happens within the Center for KANSEI Innovation at Hiroshima University’s city campus.

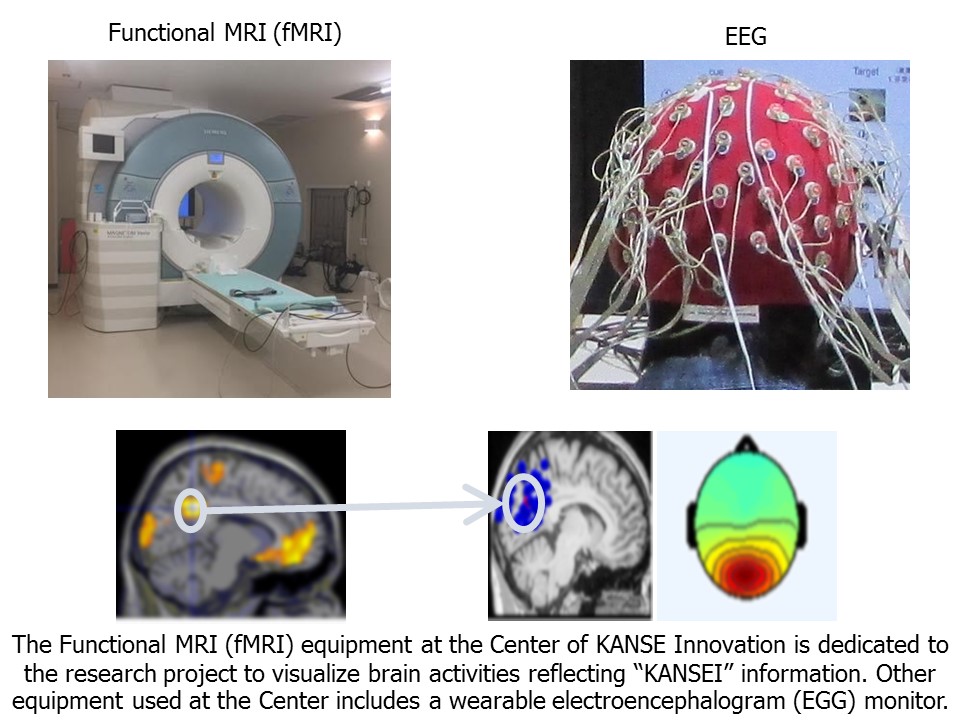

Yamawaki believes that the ability to instill a feeling of positive KANSEI gives products greater value in the modern world of extreme convenience. One project from the Center of KANSEI Innovation is using Brain Emotion Interfaces to build a car that responds to a driver’s mental state so that driving is more enjoyable. Researchers make scientific observations of professional drivers. The data include measurements of electrical signaling in the brain using functional MRI (fMRI), electroencephalogram (EEG) monitors, facial expression, eye pupil dilation, blood pressure, pulse, and grip strength on the steering wheel. All of the data are then put through artificial intelligence programs to interpret the driver’s moment-to-moment condition and respond appropriately.

The KANSEI Innovation project provides a new and major stage for the professor’s research results and a method to study the neurological mechanism that creates excitement or happiness. However, Yamawaki’s primary area of study is actually the opposite end of the emotional spectrum: depression. Specifically, Yamawaki is most interested in differentiating between what he defines as ‘subtypes’ of depression by studying the neurology and pharmacology of mental health.

DIFFERENTIATING DEPRESSION

“Young people with depression, middle-aged people with stress-induced depression, elderly people with dementia-related depression, everyone else – they are all studied together. But different types of depression may have different responses to the same treatment. We should separate them.”

Yamawaki states that the last time a novel medication for depression was approved was about a decade ago. Part of the challenge in testing the efficacy of new depression treatments is that diverse groups of patients who will likely experience diverse responses to the same treatment are analyzed together, so researchers are left with no conclusive results. By separating groups of patients into their relevant subtype, the unique groups who will or will not benefit from certain treatments can be identified.

“The future will have precision medicine for mental disorders, just like other diseases. I want to tell patients, your life and brain situation is like this, so your treatment is recommended to be this.”

Further complicating the problem of drug discovery is the competitive nature of the pharmaceutical industry. To address the problem, Yamawaki made a proposal at the July 2016 World Congress of the International College of Neuropsychopharmacology. He has encouraged a collection of pharmaceutical companies to join in what he refers to as ‘pre-competitive collaboration.’

“Now, many companies might be working on the same topic. I proposed that the companies should tell each other if they fail. With their current policies, even if they fail, they keep it a secret. Then every company can make the same failure again and again. That’s not useful,” says Yamawaki, waving away the thought of wasted time.

Companies participating in pre-competitive collaboration agree to share information about their failed research and development efforts. The hope is that with this model, the process of finding therapeutic drugs will progress faster and companies can still keep their successes as protected intellectual property to remain economically competitive.

EARLY START

This list of responsibilities has grown to be so extensive in part because Yamawaki’s academic career developed very precociously. After being born and raised in Hiroshima, Yamawaki entered the Faculty of Technology at Hiroshima University in the early 1970s.

“I am totally a Hiroshima person,” he says with pride.

As a first year student, he saw how the global crisis in oil prices affected the career prospects of other engineering students and decided to change his area of study. He switched to medicine and went on to complete a two-year residency program in psychiatry at Hiroshima University Hospital. He then spent a year abroad in Seattle, Washington, USA to study pharmacology and add an international perspective to his career. When he returned to Japan, he began working as a psychiatrist at Kure Hospital, in a port city about 26 kilometers (16 miles) southeast of Hiroshima. He also continued studying pharmacology while working and eventually received a PhD from Hiroshima University.

Yamawaki earned both medical and PhD degrees from Hiroshima University. He investigates the physical causes of mental health conditions like depression and continues to serve patients as a psychiatrist.

“In 1989, I was 35 years old, the Berlin Wall came down, and at about that time I received a message from a professor at Hiroshima University. He knew of my work and he thought psychiatry needed more scientific study, so he asked me to apply for an open professorship position. I thought, ‘Why? I am so young.’ But applying would be good experience, so I did it. Then maybe two or four months later, I got a message: ‘You are selected,’” Yamawaki recalls. Then, speaking quietly, he continues: “I felt very surprised… but that is how I came back to Hiroshima in 1990.”

Yamawaki was the youngest full professor at Hiroshima University. He has consistently used a neuroscientific approach to study mental health conditions and has seen societal opinions about mental health change over time.

“When I started, there was very strong stigma against mental health issues. It’s still a big problem, but these disorders are so common. Not just in Japan, but all over the world.”

Yamawaki recognizes that global economic issues similar to those that motivated his own shift in academic focus are still relevant to today’s university students. His advice to students: “Take it easy. Now-a-days, people have loss of future, loss of hope. But if we have hope, we can deal with stress. Motivational stress is positive, and you should avoid negative-spiral thinking stress.”

STEPS FORWARD

Although the ‘black box’ of the human brain continues to be a uniquely mysterious aspect of human anatomy, meaningful advances have been made to understand mental health.

“Modern neuroimaging and other non-invasive techniques – this technology has provided major progress and really allowed our research into mental disorders like depression,” he says. Neuroimaging studies occur conveniently just across the hall from Yamawaki’s office in the Department of Psychiatry and Neurosciences. The facilities are equipped with MRI, EEG, and additional imaging tools that are dedicated to research use.

Image by Dr. Shigeto Yamawaki.

Some of the research efforts even involve patients watching their own brain activity in real time.

“A patient can see where their brain activity is low, and we say to them, ‘Go up, go up!’ Maybe thinking about certain happy memories can change brain activity. It is neuro-feedback treatment.”

Yamawaki still speaks of ongoing research projects in a way that reveals great confidence in their future success. However, he is not necessarily attached to being the person who leads the projects forever.

“I don’t worry about my career anymore. I’m 62, I’m old! Now, my job is to try to give advice and opinions. The traditional university system is not going to work in the future, but the business model will not be good for science, I think. So, we need an integrated model. I’m responsible to try to complete the paradigm shift in the way we do research so that the younger generation can benefit. If old people stay for a long time, the younger people cannot have a chance. I think we should let them try.”

After such an accomplished career, the tangible benefits of enjoyable products that respond to people’s emotions and the intangible benefits of advancing academic understanding of the neurology of human emotion will be the obvious contributions that Yamawaki has made to society. Yet it is the possibility of positive research KANSEI that he creates for future researchers that may be the most influential benefit.

Home

Home