- Title: Differentiated embryo chondrocyte plays a crucial role in DNA damage response via transcriptional regulation under hypoxic conditions.

- Authors: Nakamura H, Bono H, Hiyama K, Kawamoto T, Kato Y, Nakanishi T, et al. (2018)

- Journal: PLoS ONE 13(2): e0192136

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192136

By Margaux Phares

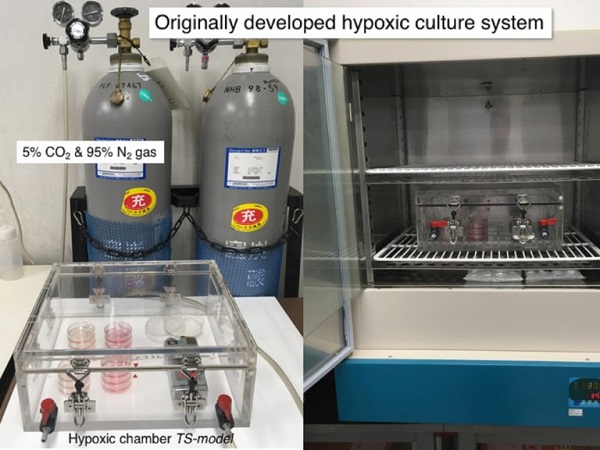

Cells growing in a hypoxic culture system. Researchers observed how one gene group controls the degree of DNA damage response in hypoxic cancer cells. (Image source: Keiji Tanimoto)

An international team of researchers found how cancer cells respond to DNA damage signaling when in low oxygen, or hypoxia. Through comprehensive gene expression analyses, the team determined how one family of genes controls DNA damage response, as well as how it weakens the effectiveness of anticancer therapies.

Our bodies have strict molecular mechanisms that help us respond to hypoxia. These mechanisms are not just limited to helping us adapt to higher altitudes when climbing up a mountain. They also arise in diseases such as anemia, diabetes, or cancers. In the case of a new study led by Keiji Tanimoto's team at Hiroshima University (HU), hypoxia indicates developments or poor prognoses of cancer.

Initially, a tumor growing within a patient depends upon oxygen and nutrients from his or her blood. Eventually, however, a tumor can outgrow this supply of nutrients and end up in hypoxia. This stage does not spell the end of growth - by changing its own metabolism, a tumor can adapt to growing in low oxygen.

"In the medical biology field, we generally knew that cells in hypoxia appeared mutated, but we never quite knew how it happened," Tanimoto said. He is the primary author of this study, as well as Assistant Professor in HU's Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine. "This led us to think that hypoxia may affect a tumor's ability to recognize and repair damaged DNA or program its cells to die."

“We hope this study leads to the development of drugs that can make tumors more sensitive to anticancer therapy.”

Hypoxic tumors tend to be resistant to anticancer treatments. Radiation therapy, for example, kills tumor cells by destroying their DNA. After exposing cancer cells to hypoxia, though, Tanimoto's group found that hypoxic cells could better resist radiation treatment than cells treated in normal oxygen levels.

To understand what was happening at the molecular level, Tanimoto's group analyzed gene expression of the hypoxic cancer cells. They were particularly interested in Differentiated Embryo Chondrocyte, or DEC. The team found that DEC levels increased in hypoxic cells, which stalled the transcription of DNA repair genes.

Without a way to signal that their DNA must be repaired, cells with damaged DNA can keep growing uncontrollably. Ultimately, the lab found that suppressing DEC2, one form of DEC, made cancer cells more sensitive to radiation treatment and restored cell death signaling.

Understanding how cancerous cells behave in low oxygen may provide new strategies for tackling cancer. "We hope this study leads to the development of drugs that can modify hypoxic signaling and make tumors more sensitive to anticancer therapy," Tanimoto said. "From our results, DEC2 could be an effective target for these drugs."

This study was conducted in collaboration with the Database Center for Life Science.

Keiji Tanimoto, primary author of this study, is Assistant Professor in Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine. (Photo credit: Hideaki Nakamura)

- Profile of Assistant Professor Keiji Tanimoto

- Official website of the Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine

- Find more Hiroshima University research news on our Facebook page

Norifumi Miyokawa

Research Planning Office, Hiroshima University

Email: pr-research*office.hiroshima-u.ac.jp (Please change * into @)

Home

Home