On February 1, 2013, Hiroshima University established two new programs: the “Distinguished Professors” (DP) program and the “Distinguished Researchers” (DR) program. Individuals who are part of these programs are recognized as senior and junior faculty members respectively, who are engaged in extraordinarily distinguished research activities.

Interview of Distinguished Professor Junko Tanaka

Aiming to eliminate viral hepatitis in Japan and worldwide using evidence from epidemiological research on hepatitis viruses.

Epidemiology, a medical discipline that focuses on human populations

I specialize in a field called epidemiology. Epidemiology is an academic discipline that falls under the “social medicine” branch of the three main branches of medicine, with the other two being clinical medicine and basic medicine. When a human population experiences some kind of emergency event, for example, the COVID-19 pandemic, the first job of epidemiologists is to determine the human impact, which in the case of the pandemic would be the scale and extent of infection. Then, the next jobs of epidemiologists are to research the cause of the disease, to ascertain the natural history of the event (e.g., disease progression) while simultaneously determining the need for countermeasures. And finally, if countermeasures are indeed necessary, to propose a plan or present evidence for drafting social measures.

For many years now, I have researched hepatitis viruses and the epidemiology of viral hepatitis and liver cancer caused by these viruses. I began working on this research about 30 years or so ago, when one of the members of the Japanese group that was competing with other countries to research the hepatitis C virus (then called non-A non-B hepatitis) arrived at Hiroshima University as a professor Department of Hygiene (currrent: Department of Epidemiology, Infectious Disease Control and Prevention) where I was an assistant professor, and he and I started doing research together with his guidance. The time we started our research at Hiroshima University coincided exactly with the discovery (in 1989) of the genetic sequence of the hepatitis C virus, which is thought to be responsible for the majority of hepatitis cases transmitted through blood. In the area of hepatitis C virus, which is transmitted from person to person through blood, I have continued to conduct surveys and research on topics such as the frequency of infection routes, prevalence rates and new infection rates in the general population, pathological natural history, progression rate to liver cancer, screening strategy, and measures against hepatitis.

Electron micrographs of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV)

When conducting epidemiology research, it is very important to collect proper data with as little sampling bias as possible, in order to determine epidemiological indicators. For example, to determine the percentage of people with persistent hepatitis C and B infection (i.e., prevalence) nationwide, I obtained nationwide data (data on first-time blood donors from the Japanese Red Cross Society and data on nationwide hepatitis testing from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [MHLW]) as the principal investigator of an Epidemiological Research group supported by the MHLW Policy Research program. These results are cited in international comparisons as reference values for the status of viral hepatitis infection in Japan.

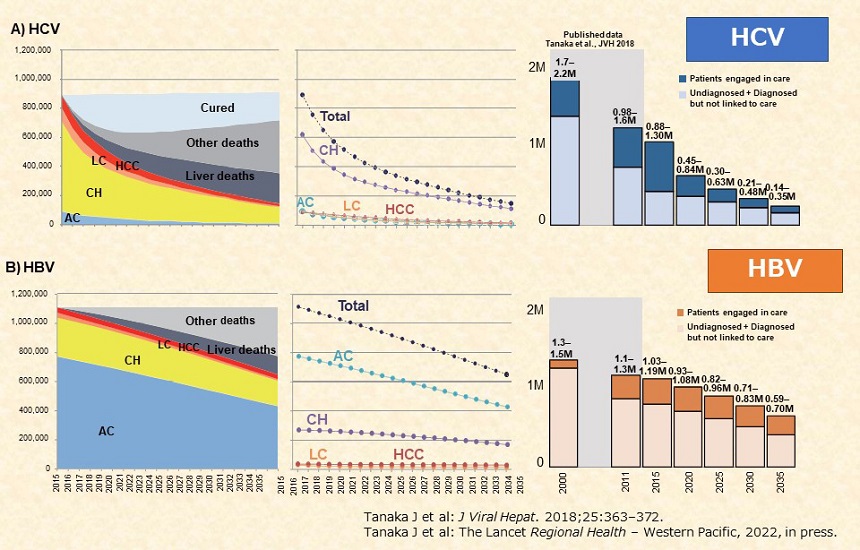

Aiming to eliminate hepatitis C worldwide by 2030

Japan has one of the high mortality rates from liver cancer of all countries in the world. The number of liver cancer deaths in Japan began increasing steadily around 1970, peaked at over 30,000 per year in 2002, and then began declining. The current figure is about 25,000 deaths per year. In the past, alcohol consumption was thought to be the main cause of liver cancer, but in reality about 60-80% of liver cancer deaths (in 2002) were caused by persistent hepatitis infection, mainly with hepatitis C virus but also with hepatitis B virus. In many cases, persistent hepatitis B and C virus infections are asymptomatic, with patients developing liver cancer or other symptoms decades later. This makes it difficult to determine infection status and the natural history of the disease after infection. Therefore, we fitted a variety of small and large sets of data on patients with persistent hepatitis C virus infection who are undergoing long-term follow-up at medical institutions to a mathematical model (Markov model) to estimate the incidences of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and liver cancer each year after infection. This analysis revealed that infected patients who do not develop clinical hepatitis by age 40 are at high risk of developing liver cancer in the next 30 years if left untreated. In other words, even in people whose condition has not yet progressed, awareness of infection status may prevent progression to severe liver disease by allowing for early treatment. We also found that the number of people infected with hepatitis B and C virus, in epidemiological terms "the burden of disease," including those who area asymptomatic and unaware of their infection status, was 2.4 to 3 million people in the year 2000, and 80% of those were over 40 years old. These findings were one piece of evidence used to support the introduction of hepatitis testing (for hepatitis B and C viruses) into population-based screenings for adults aged 40 years and older. The Basic Act on Hepatitis Measures, which went into effect in 2009, has the slogan, "get tested at least once in your lifetime." National surveys on screening rates that we conducted in 2011, 2017, and 2020 showed that approximately 70% (hepatitis B virus) and 60% (hepatitis C virus) of Japanese citizens have been tested, and these percentages are rising.

Hepatitis C was once an intractable disease that causes liver cancer with no vaccine available to prevent it and no drug to effectively eliminate the virus. However, in recent years the situation has changed dramatically with the development of oral medications that eliminate hepatitis C virus from the body with minimal side effects. Backed by increasing adoption of countermeasures and treatment such as the HB vaccine and effective oral anti-HCV drugs, the World Health Organization (WHO) has set a goal of eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030. Hepatitis C is expected to become the second infectious disease eradicated by humankind, the next one after smallpox. The 2020 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three American and British scientists whose discovery of the hepatitis C virus later enabled diagnosis of the disease and development of antiviral drugs to treat it. It is a great achievement for humanity that we have come so far to where we can set such a goal of eradicating a virus when scarcely over 30 years have passed since its discovery.

Estimated and projected numbers of people with persistent hepatitis virus infection in Japan (2015-2035), illustrating that both hepatitis C virus (HCV) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) are decreasing

Teaching epidemiological research to young physicians and researchers in Asia and Africa

Japan has been seeing a decrease in persistent hepatitis virus infection, but the regions of Asia and Africa have the highest prevalence rates in the world. I am currently hosting Japanese government-sponsored students from Cambodia, Vietnam, and Burkina Faso at Hiroshima University and teaching them how to conduct epidemiological surveys and analysis while conducting international collaborative research on the epidemiology of hepatitis viruses. These students are outstanding individuals who will work to better the health of people in their home countries as frontline physicians, researchers, and medical administrators upon returning home. My team, with the help of these students, is also conducting surveys abroad, which is giving us a great sense of fulfillment to be participating in global health efforts. Current collaborative international research projects include genetic analysis of hepatitis viruses, epidemiological and prevalence distribution, and the effectiveness of measures to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HBV.

The field of epidemiology deals with large volumes of data and samples, each of which represents the precious individual life of a person or patient. With constant respect for the weight of this data, I will continue to work with researchers of various specialties to eliminate liver diseases from the world.

Finally, for the past two years or so I have also been involved in epidemiological research on COVID-19. The feeling of planning and conducting surveys on COVID-19 while the prevalence, severity, and natural history of the disease remain unknown reminds me of how I felt during conducting hepatitis survey after the discovery of the hepatitis C virus. The academic and research field of epidemiology is one of the important fields for disease management, and I would like more people to know about it.

Scene from a field meeting for an epidemiological study on mother-to-child transmission of hepatitis B virus in Cambodia

Home

Home