Research Article: Masuda, K., Urabe, Y., Ito, M. et al. J Gastroenterol (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00535-019-01596-4

By Emma Buchet

A layer of cells that look like normal stomach lining on top of sites of stomach cancer can make it difficult to spot after removal of a Helicobacter pylori infection. In a recent study, researchers from Hiroshima University have uncovered the origin of this layer of cells: it is produced by the cancer tissue itself.

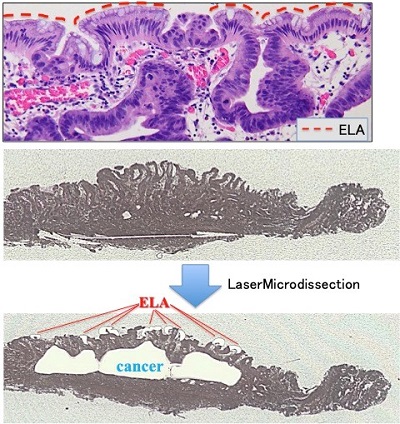

Extraction methods for cancerous tissue, normal tissue, and ELA. The red dotted line indicates epithelium of low-grade atypia (ELA) covering the surface of gastric cancer tissue in upper image. ELA (Red) and cancerous tissues (Blue) extracted by Laser Microdissection in lower image. Credit: Hiroshima University.

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a type of bacteria that lives in people’s stomachs. To survive the harsh environment these bacteria can neutralize stomach acid. H. pylori is the leading cause of stomach cancer, one of the most common types of cancer which can have a low survival rate. The bacteria cause inflammation by injecting a toxin-like substance into mucosal cells that line the stomach. This destruction and regeneration of these cells can lead to the development of stomach cancer.

In this study Professor Kazuaki Chayama, from Hiroshima University Hospital, and his team found the origins of a strange layer of cells that was present on stomach cancer sites after treatment of H. pylori. This layer, called ELA (epithelium with low-grade atypia), resembled normal mucosal cells that line the stomach and acted like a mask to hide stomach cancer. Up to now, researchers were not sure where this layer came from.

“It was very interesting scientifically to find that that cancer reoccurs even after eradicating causal bacteria.” says Chayama.

A H. pylori infection is cured after a course of antibiotics that leave reddish depression in the stomach.

“H. pylori eradication affects the regeneration of gastric mucosa. After eradication there are many reddish depressions in the stomach, most of them are not cancer. It is difficult to identify the ELA mucosa from amongst the regular mucosa.” explains Chayama.

The research group conducted a preliminary study on 10 patients after gastric operations and looked for this layer of cells. The ELA cells’ DNA was intensively studied and was found to be identical to stomach cancer cells. ELA was concluded to come from the stomach cancer tissue itself.

These findings could mean that even after getting rid of H. pylori there is still a risk of stomach cancer for some patients. Stomach cancer can be difficult to spot due to its location and the fact that the disease can progress slowly. This is not helped by ELA that masks cancer after the causal factor is removed.

Chayama stresses that clinicians should be aware of this layer, so they don’t miss potential sites of stomach cancer and that it is important for patients to continue having check-ups even after finishing treatment for H. pylori.

Details of the findings can be found in the team’s paper, published in the Journal of Gastroenterology on June 13.

Funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number: 16K19379)

- Profile of Professor Kazuaki Chayama

- Find more Hiroshima University research news on our Facebook page

Norifumi Miyokawa

Research Planning Office, Hiroshima University

E-mail: pr-research*office.hiroshima-u.ac.jp (Please change * into @)

Home

Home