On February 1, 2013, Hiroshima University established two new programs: the “Distinguished Professors” (DP) program and the “Distinguished Researchers” (DR) program. Individuals who are part of these programs are recognized as senior and junior faculty members respectively, who are engaged in extraordinarily distinguished research activities.

Distinguished Professor Hideki Ohdan outside the Department of Gastroenterological and Transplant Surgery at Hiroshima University. Ohdan had the original idea for the logo (left side of image) using the department’s initials, GTSH, in an artistic interpretation of internal organs: G and T representing the hepatobiliary system, S representing the stomach, and H representing the colon.

Distinguished Professor Hideki Ohdan identifies himself as a “surgeon scientist.” He grew up in Hiroshima city and completed a Medical Degree in 1988 and a PhD degree in 1997, both from Hiroshima University. Now, he leads an active medical practice and research laboratory at Hiroshima University Hospital. His career has focused on removing biological barriers to match organ donors with patients who need organ transplants. This project is driven by the immediate needs of clinical patients, but involves solving a larger scientific mystery: how does the immune system recognize its own body as native cells to ignore and recognize foreign cells as invaders to destroy? Manipulating this sense of self could reduce organ transplant recipients’ need for lifelong medication and enable the immune system to eliminate cancer cells.

OVERCOMING ANTIBODY-MEDIATED REJECTION

Ohdan spent three years at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) between 1997 and 2000 and also worked briefly in Florida at the University of Miami. While at MGH, he investigated the processes of antibody-mediated rejection, which is the medical condition that traditionally requires organ donors and recipients to have the same blood types. Ohdan used xenotransplantation, transplants of cells or whole organs between different species, as a model to understand antibody-mediated rejection between human patients.

“My work at MGH was to study organ transplants from pigs. The biochemical process of why humans will reject pig organs is similar to why they will reject organs from a donor of a different blood type. Carbohydrate antigens on the surface of the cell are what start the immune reaction in both cases.”

When Ohdan first started his career as a transplant surgeon, potential donor-recipient pairs whose blood types did not match were said to be ABO incompatible and transplants would be canceled. The four major blood types (A, B, AB, O) possess different antigens on the surface of blood cells; the immune system can start a deadly reaction if it reacts to these antigens as foreign molecules.

In 2005, that research project on antibody-mediated rejection helped lead to the first successful organ transplant between a donor and recipient with incompatible blood types. Now, B lymphocytes, a type of a white blood cell and part of the immune system, can be specifically destroyed by an antibody medication, thereby eliminating the source of antibody-mediated organ rejection due to ABO incompatibility.

“Now we have successfully performed about 20 liver transplants and 50 kidney transplants between donors and recipients with ABO-incompatible blood types. The best moment is when the first clinical trial patient leaves the hospital successfully. That is the reward for being a surgeon scientist,” says Ohdan.

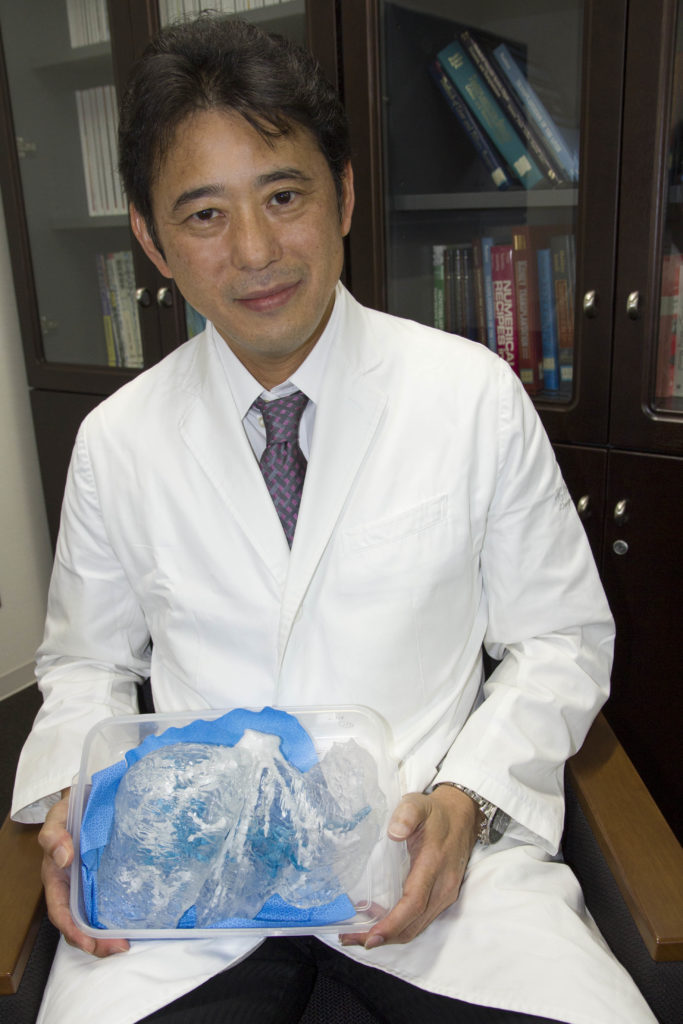

Ohdan with a model liver created by the Hiroshima University School of Dentistry using 3D printing. The model (resting on a blue towel inside a plastic box) has a soft, flexible texture and blue and white tubes on the inside represent major veins and arteries. Models like these are created using MRI or CT scans of each living donor’s liver prior to surgery. Ohdan and the transplant team plan their surgical approach based on each donor’s unique anatomy.

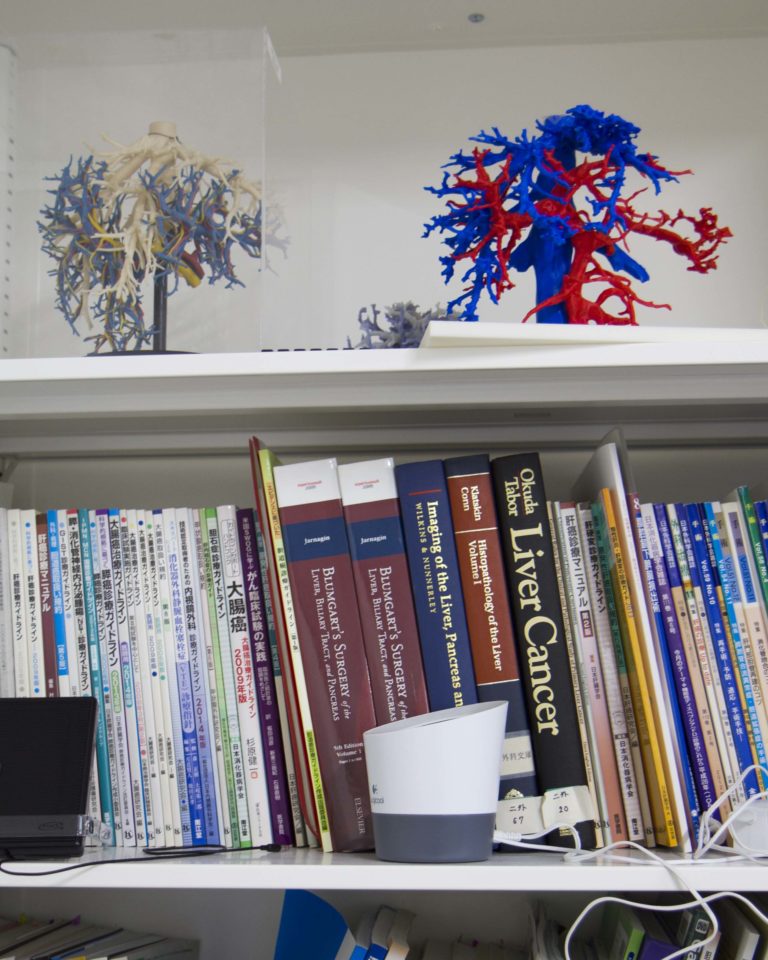

Prior to the advanced 3D printing techniques that allowed for the creation of full livers, Ohdan’s liver transplant team used 3D printed models of only the veins and arteries inside a donor’s liver. Now, some of the old models decorate a bookshelf used by an associate professor.

HOMETOWN TEAMWORK

Ohdan has worked at Hiroshima University Hospital since returning to Japan in 2000.

“The great thing about working at Hiroshima University is that my laboratory is here next to my neighbors. Maybe for people who are not Hiroshima natives, they cannot truly understand this. But I am motivated to work with and for my neighbors. I know Hiroshima people can all relate to each other.”

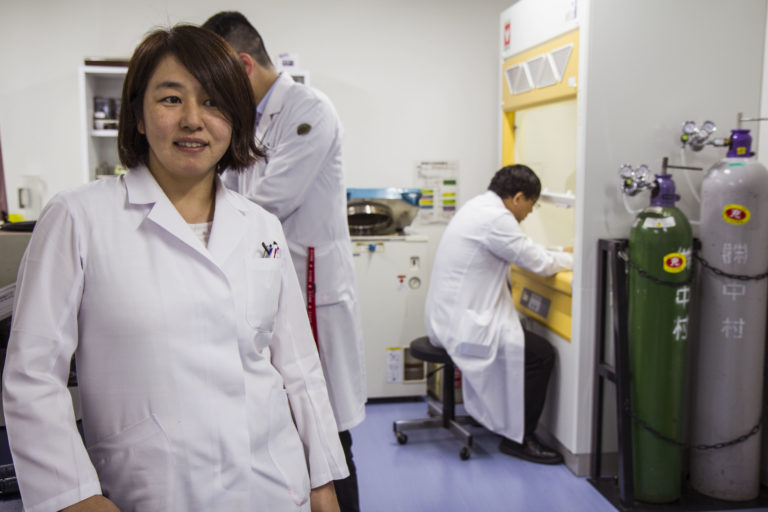

The strong sense of community that Ohdan fosters within his laboratory is evident in the dedication of some of his collaborators. Associate Professor Yuka Tanaka started working in Ohdan’s lab in 2000 as a laboratory technician. She has since completed PhD and post-doctoral studies and continues to work in Ohdan’s laboratory at Hiroshima University, studying cancer and viral infection research related to liver transplantation.

Ohdan’s strong connection to the local community has not stopped his commitment to improving care for patients around the world. Since 2012, his lab has hosted medical doctors from Kazakhstan who complete research projects related to liver or cancer research and earn PhD qualifications before returning to their home country.

This miniature statue of the Golden Warrior, a national symbol of Kazakhstan, was a gift from officials in Kazakhstan to Ohdan to recognize his contribution to medical practice and research in the country. Ohdan visited Kazakhstan to provide training and advice to other transplant surgeons and continues to supervise PhD projects of future surgeon-scientists from Kazakhstan in his laboratory at Hiroshima University.

Ohdan helps to foster a sense of community within his lab by arranging an annual trip to watch a baseball game of the local Hiroshima Toyo Carp team.

“Oh, I am a crazy Carp fan!” says Ohdan. The professional baseball team endured a losing streak that started in 1991 and was finally broken in 2016, but the avid local fan base never abandoned the team. Ohdan remembers attending games with his family as a child, but he watched what may have been his most notable game during his annual trip with the lab group in 2013.

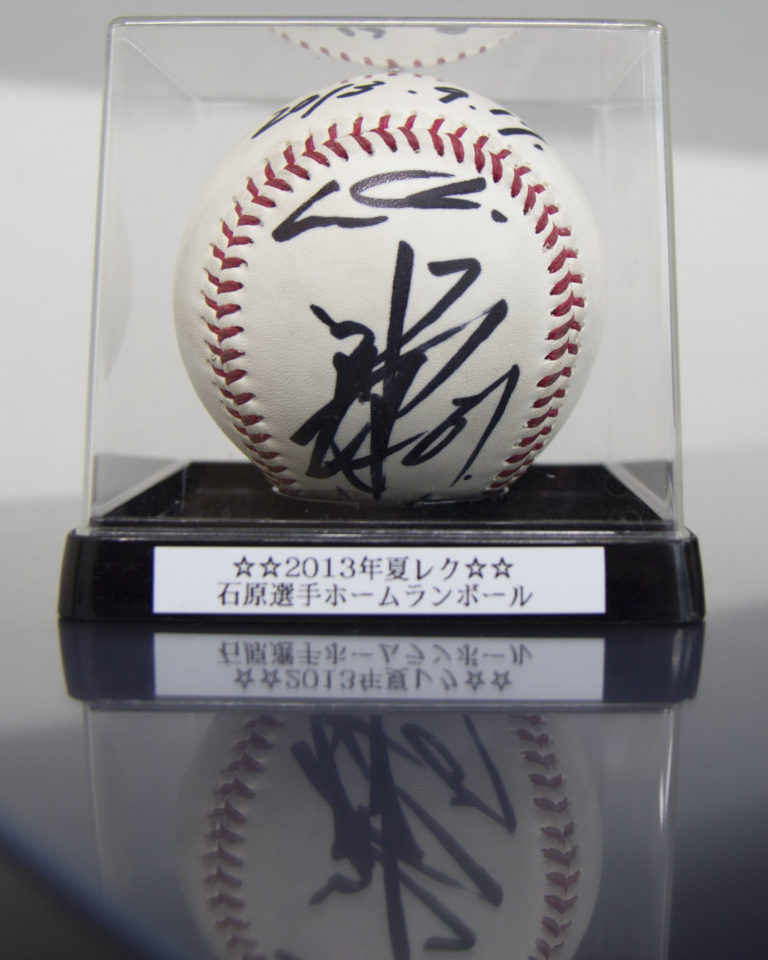

The autographed home-run ball hit by Yoshiyuki Ishihara, the catcher of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp baseball team, at the September 17, 2013 game. Ohdan, a Hiroshima native and passionate Carp fan, keeps this memento from the annual laboratory baseball game trip in his office at Hiroshima University.

“It was the end of the ninth inning, the Carp had two outs already, and Ishihara was up to bat. He is a good catcher, but everybody knows he is not the best batter. We started getting ready to leave because we expected to lose again. But Ishihara hit the ball and scored enough runs that the Carp won! When he hit the ball, it flew right to where we were sitting.”

Ohdan now keeps the autographed baseball in a cabinet in his office. His deep value of the importance of community is also evident in his emphasis on teamwork for successful scientific and medical outcomes.

“For surgeon scientists, making a successful team is very important. We have experts in science, experts in clinical practice, and we have people who do both. Achieving a mix of these three different experts in the team – this is what makes our work efficient and gets the good results,” Ohdan asserts, listing the keys to a productive research group.

He quickly adds, jokingly, “But don’t tell anyone the secret!”

LIFE SAVERS IN NATURAL KILLERS

One of the most exciting medical advances that Ohdan’s work has helped make possible is the use of Natural Killer cells to prevent the spread of cancer in liver cancer patients after they receive a liver transplant. Natural Killer cells are a type of immune cell that can recognize and destroy stressed cells, like cancerous or virally infected cells. Patients with liver cancer are more likely to have their cancer return after a liver transplant. Their immune response is reduced by the immunosuppressant medication that they take to ensure their body accepts the donated liver, so their body’s normal response to cancer or infection is reduced.

Before a donated liver is placed into the recipient’s body, the liver is drained of all of the donor’s blood to prevent dangerous blood clots. Ohdan’s team noticed that about 50 percent of the lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell and part of the immune system, within that drained blood are Natural Killer cells. Within normal circulating blood, only about 20 percent of lymphocytes are Natural Killer cells.

After isolating those liver Natural Killer cells from the blood drained out of the donated liver, researchers can activate the cells with a three-day chemical treatment in the laboratory. The activated cells are then given to the organ recipient patient via a normal blood transfusion.

“We started the laboratory research for this project in 2000, and then human trials began in 2006. Now it is clinically approved as a normal method to effectively reduce cancer reoccurrence in these patients, and we are studying the same method to eliminate post-transplantation blood infections,” says Ohdan.

Post-transplantation blood infections are common in liver transplant patients, regardless of their cancer status. When monitoring transplant patients who received the Natural Killer cell treatment to reduce their risk of liver cancer recurrence, Ohdan’s team noticed that the patients did not develop blood infections. In 2011, a member of the research team met with Ohdan’s former co-workers at the University of Miami to begin human trials that have now reached Phase II clinical trials in the United States.

“Fewer than 10 percent of patients develop a blood infection after receiving the infusion of Natural Killer cells isolated from the blood of the donated liver. We are completing more research to better understand the basic science of how Natural Killer cells have these medical effects so we can use them to treat other types of cancers or infections,” says Ohdan.

BALANCE AND REWARDS

In addition to his medical and research duties, Ohdan also teaches introductory courses for medical students studying at Hiroshima University Hospital.

“Doing clinical rounds to check on patients is an opportunity for teaching students, so there is some multitasking during the day while I am doing medical work. But after 5pm when my medical and teaching duties are done, that is finally my research time to focus on experiments.”

Ohdan is currently the leader of the Department of Gastroenterological and Transplant Surgery at Hiroshima University Hospital. Portraits of the five professors who previously led the department, then known as the “Department of Surgery II,” hang in his office. From left to right, the professors are Dr. Kunio Kawaishi, Dr. Retsu Hoshino, Dr. Haruo Ezaki, Dr. Kiyohiko Dohi, and Dr. Toshimasa Asahara.

Ohdan says that the inspiration for his late-night research often comes from the challenges presented by his medical work.

“I believe good ideas come from critical clinical situations. The need to find solutions forces us to think and talk about many possibilities. The ideas to solve that one clinical situation can become the source of many future research projects.”

Ohdan describes the ultimate goal of his research as finding the balance between a patient tolerating a transplanted organ without lifelong medication and a patient’s immune system rejecting the organ. He moves his arms in a see-saw motion, imagining finding this balance and remarks, “That would be great.”

Views of the Department of Gastroenterological and Transplant Surgery staff and facilities. Image provided by Dr. Hideki Ohdan.

The medical staff members of the Department of Gastroenterological and Transplant Surgery in Hiroshima University Hospital. Image provided by Dr. Hideki Ohdan.

To read more about all of Distinguished Professor Hideki Ohdan’s research projects, explore a full list of his academic publications by visiting his university faculty information page here.

<http://seeds.office.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/profile/en.eb4c219a3f01af34520e17560c007669.html>

An older interview of Distinguished Professor Hideki Ohdan from earlier in his career is available from the PR Group here.

<https://www.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/en/research/now/no5>

Home

Home