Ideas-mining is a problem-solving tool developed by the University of Münster almost 20 years ago. The goal is to tackle a problem from various approaches, sometimes using unusual methods. These methods can then be applied in numerous areas, from business to scientific research, and even human resources. Creativity is the focus here, as Ideas-mining aims to disrupt the 9-5 working format, which its creators say is harmful to the creative process.

“Ideas mining is a sort of adult playfulness” Bauhus

Two delegates from the University of Münster: Mr. Wilhelm Bauhus and Ms. Lena Wobido, visited Hiroshima University to explore and exchange some methods of Ideas Mining. This was the third visit to HU for Bauhus.

Lena Wobido (left) and Wilhelm Bauhus (right) at the Bioinspiration Ideas Mining workshop 16 March 2019

This session’s theme was “bioinspiration”. Bioinspiration means to take inspiration from nature and use it to solve problems and think innovatively. A good example is the shinkansen bullet train here in Japan, which was designed using biomimicry (copying nature). Engineers designed the nose of the train based on a kingfisher’s beak and pantograph (the part that connects the train to the wire above) on owl feathers to reduce the noise of the train as it speeds through the countryside. Nature builds structures using the resources available and companies, researchers and engineers have been inspired to copy its structures and processes.

“Nature works efficiently, resiliently and sustainably,” Wobido.

On March 16, the Science Communication team and other faculty members from HU joined the University of Münster along with members from the Hiroshima University of Economics on a trip to Miyajima Island, the site of the famous Itsukushima Shrine.

View of the shrine from the seminar room and a closer view of the famous monument

Bauhus and Wobido introduced the participants to the idea of bioinspiration. Bioinspiration has actually been around for a long time. Leonardo da Vinci was bioinspired by a dandelion seed and sketched his own version of a parachute. Neanderthals were shown to have used pyrolysis (using fire) to create tar when making arrows. Recently, bioinspiration has been used for more than just taking natural structures and applying them to technology or art. Bauhus explained how companies are interested in bioinspired leadership structures or marketing processes. He asserts that we need creative detours for work, and we should start “thinking with [our] senses”.

Examples are the best way to ensure the participants are interested in and understand a new concept. In this case, Bauhus and Wobido used bionarratives: creating a story around nature and its applications. Some examples from the session included how slime mold can be used to inspire subway systems, dandelions can make tires and how tiny creatures called diatoms made nitroglycerine safer and transportable.

Bauhus holding a stalk of rye coated in ergot mold. Ergot was infamous for causing people to become ‘insane’ (notably in France and in Salem, Massachusetts which may have caused many innocent people to be accused of witchcraft). This mold inspired a lot of European art and is the basis for LSD.

Bioinspiration on Miyajima Island

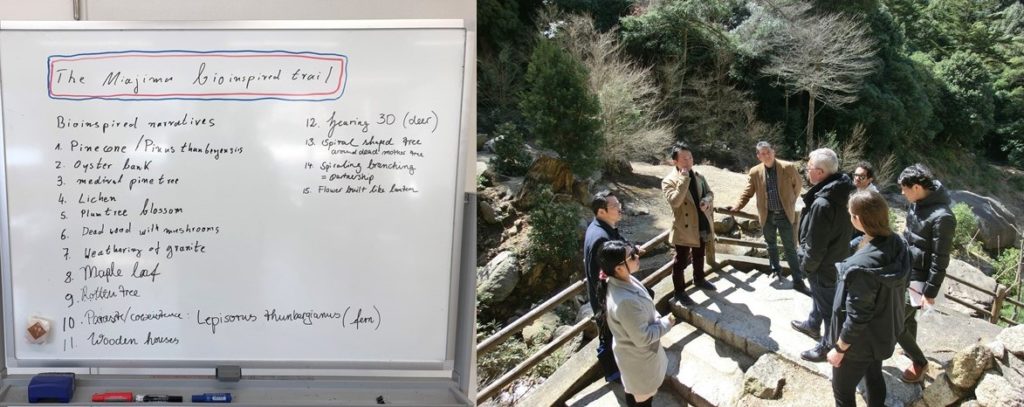

The participants were split into teams and taken to bioinspiration spots on Miyajima island, while Bauhus and Wobido described why they were bioinspirational. Each stop on the bioinspiration trail told a story (or bionarrative) about how that structure or creature lent its innovations to humankind.

The participants of the workshop walked along a “Miyajima bioinspired trail”, adding to the stops made by Bauhus and Wobido. The good weather made the stunning natural landscape even more inspiring!

Here are some of the bioinspirations the group found on Miyajima:

Nature as an innovator:

Pine cones found all over the world are innovatively designed. They open and close according to the weather: they open when conditions are dry and close in wet conditions. This technology is used for smart textiles to simultaneously keep out rain and let sweat escape in the same fabric. Not only is this applicable for the actual products but it is also used for marketing research as weather patterns influence consumption.

Nature as a cleaner:

Lichin (light green mark on the rock in the right photo) has long been used as an indicator of air quality. But this is not just in the past. Recently car companies in Germany had a major problem with emissions and the German cities have mapped lichen to test air quality. As for clean water, a small tasty creature could help us with that. Oysters (top left photo) filter 200L of water a day and they can be used to clean sea water. They are very effective cleaners and do not require any additional energy input.

Nature as a cycle:

Bauhus showed us a large granite boulder, a common type of rock found in Japan. Rain mixes with lichens and organic molecules to create chemical erosions that can cause landslides. This is very important for the prediction and prevention of destruction from natural disasters. Hiroshima prefecture mapped 50,000 potential landslide sites after being hit with devastating floods in July 2018. However, destruction and decay can also serve an important purpose. The is “no rubbish in nature,” says Wobido, using trees as an example. Blossoms fall and are degraded into their nutrients that are used for other organisms. Dead trees can also become habitats for many organisms such as mushrooms and small animals.

The participants of the workshop will now take the methods they learned and try to apply them to their respective fields, from language-teaching to research planning. We would like to thank the visitors from the University of Münster for sharing their knowledge with us!

Workshop Members (left to right): Norifumi Miyokawa (HU), Emma Buchet (HU), Takeshi Miyahara (Hiroshima University of Economics), Wilhelm Bauhus (University of Münster), Lena Wobido (University of Münster), Atsushi Nagai (HU), Sally Chan (HU) and George Harada (Hiroshima University of Economics).

Originally written by Emma Buchet

Home

Home