By Emma Buchet

When people think of nature in Japan they think of cherry blossoms or Sakura (桜). These beautiful blossoms are culturally important for the Japanese people, as the blossoms symbolize “human life, transience and nobleness”. Every year, thousands of people gather at Sakura hotspots to take part in Hanami (花見) or cherry blossom viewing.

So why are they so important and why are we interested in them as more than pretty flowers? The lifetime of these flowers is very short; the blooming season in Japan lasts for about 2 weeks to a month. The blossoms of each tree last for about 3 to 7 days says local professor Hiromi Tsubota, Associate Professor in Miyajima Natural Botanical Garden, Graduate School of Science at Hiroshima University.

Hatsukaichi city in Miyajima (Photo by: Digital Museum Hiroshima)

The reason why they bloom all together is more scientific than we think, explains Professor Tsubota.

"Synchronization of each cherry blossom, because they are genetically closely related each other originating from breeding by humans or in nature. The other reason is selection by humans for gardening use."

So human selective breeding has greatly influenced these trees. Professor Tsubota explains that the cherry blossoms in most of Japan are not wild species but a hybridization (mix) of different species. This is explored in a research article that traces the origins of these blossoms using molecular analysis[1]. These species now tend to bloom all at the same time, depending on temperature, sweeping across Japan in March or April.

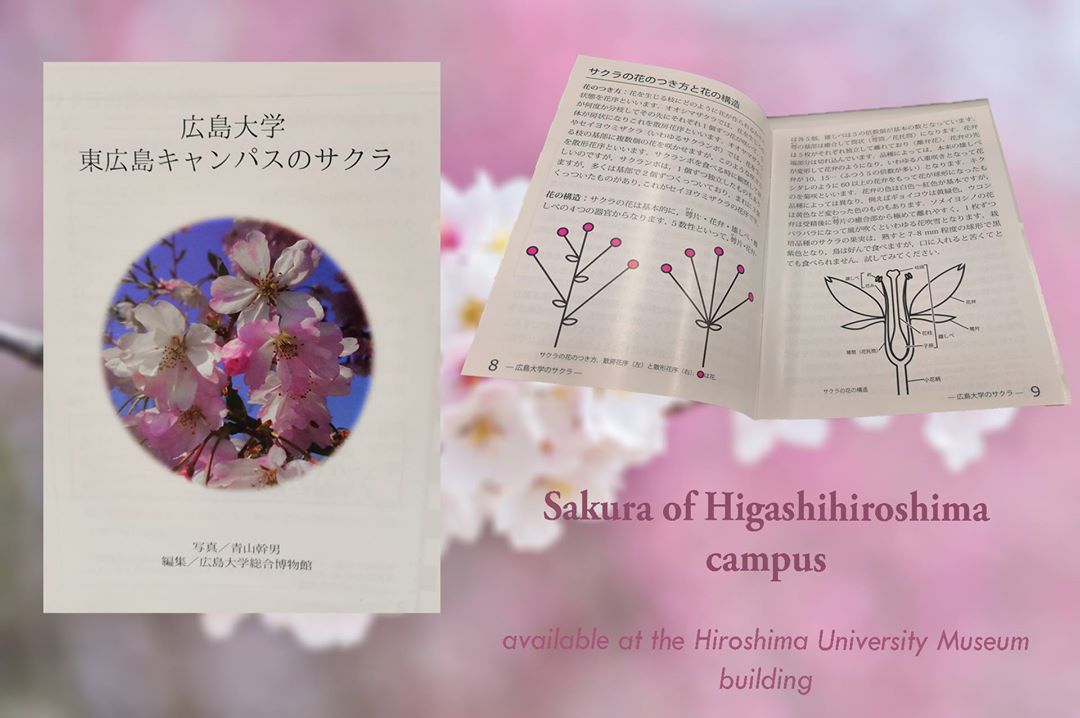

Around Hiroshima University there are 66 varieties of cherry blossoms across the Higashi-Hiroshima campus, which can be seen in the booklet Sakura of Higashihiroshima campus (in Japanese). In spring and autumn, this transforms the campus into a colorful landscape.

So now we know that genetics play a role in the short blooming season. Will that make your Hanami more enjoyable this year?

For more scientific and research updates follow us on Facebook at Hiroshima University Research and on Twitter at HU_Research.

[1] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11295-014-0697-1

Home

Home