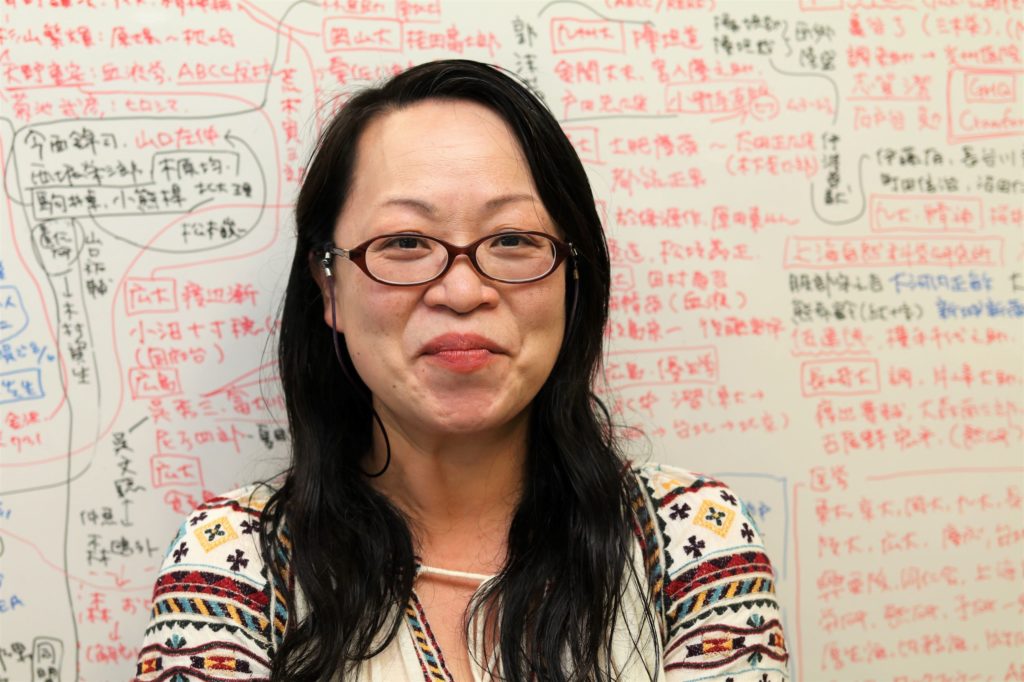

As an archivist at Hiroshima University, Kubota works to preserve the records of those who perished, as well as the memories of those who survived, the world’s first nuclear weapon attack. (Photo: Hiroshima University)

In the summer of 2015, when she moved from Tokyo to Hiroshima, Akiko Kubota was surprised by two things: One, the love and excitement towards the Hiroshima Carp baseball team; and two, the fraught relationship concerning the atomic bomb and the people of Hiroshima. August 6, 2018, marks the 73rd anniversary of the day the United States detonated an atomic bomb over the city of Hiroshima, killing over 700,000 people.

As an archivist at Hiroshima University’s Research Institute for Radiation Biology and Medicine (RIRBPM), Kubota works to preserve the records of those who perished, as well as the memories of those who survived, the world’s first nuclear weapon attack.

Tell me about a typical day working as an archivist.

I read five kinds of newspaper every day. I will pick up articles about issues of atomic bombs, nuclear power plants, and nuclear weapons and use them for research. Since my office is a research institution, we get lots of academic correspondence. I receive questions about the history, materials, and records on the atomic bombing. There are also many inquiries about medicinal investigation and record of treatment for bomb survivors.

I also read lots of literature to learn more about how to best store these records. I make sure they are kept in optimal temperature and humidity. Even the type of storage material is important. An envelope or box we use needs to be one made of paper suitable for preserving old materials.

I think that science has to explain to society whenever necessary. However, science without social consciousness is unnecessary in this world.

What kinds of materials are in the archives?

They are really varied! One example is a collection of rare books on atomic bombs. Another is medical records of atomic bomb survivors that the United States seized and were returned to Japan in the 1970s. It is very meaningful that Hiroshima's atomic bomb medical data is at the medical research institute of the university. My job is to effectively utilize the record of scientific history research as a social resource. I think that this is the contribution and responsibility of the university to local people.

It sounds like sensitive work.

Yes, we often must consider the ethical and legal implications of our work. Many of the materials I deal with are related to the ravages of atomic bomb exposure. It is not an exaggeration to say that there are as many problems as the number of documents.

For example, bomb survivors’ medical data is important for advancing science and medicine. They are the evidence of research. With this, I must protect the privacy and feelings of the survivors and their families. By the same token, these archives will be the evidence of reanalysis.

I think that science has to explain to society whenever necessary. However, science without social consciousness is unnecessary in this world.

Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, where Kubota and many others have attended the memorial ceremony commemorating the day the atomic bomb was dropped. (Photo: Vladimir Mokry)

What do you think people’s attitudes are on moving forward since the disaster?

No one wants to forget. Rather, they do their best in keeping memory. Even all this time later, new programs have come into place. For example, a program to train storytellers to talk about the experiences of the bomb survivors and pass them down to future generations started last year.

Sometimes it seems that Hiroshima and people in Hiroshima are saturated with memories and an idea that the atomic bomb is the most significant thing that happened here. At the same time, though, what happened on that day seems to keep the people of Hiroshima together in peace.

A few months after I moved to the city, on August 6, 2015, I attended the peace memorial ceremony. At 8:15AM, we all prayed silently. But, I couldn’t do it. I was scared and opened my eyes. I looked up to the sky to check for the Enola Gay, the plane that carried the bomb. It wasn’t there. Just the blue sky, which opened overhead. I was relieved and closed my eyes. It was my first experience, but here in Hiroshima, they have reflected on this experience over 70 times.

What does this mean for the archive?

For the future, I think that it is necessary for Nagasaki and the research institutes in Hiroshima to cooperate in order to develop comprehensive atomic bomb survivor medical database and archives. And, I think that in addition to working with Fukushima, we should develop radiation exposure data and archives.

By developing an organized and well-collected archive, we can advance with information that is more accurate and enlighten the world about the effects of the atomic bomb. 73 years has been such a long time. But, that also means we still have a very long future of us.

Originally written by Margaux Phares (Hiroshima University Science Communication Fellow)

Originally published in August 2018

Home

Home