By Hiroshima University Department of Public Relations

Study shows evidence of the “wandering mind’s” double-sided effect on headache.

Highlights

- People with a tendency toward repetitive negative thinking, such as worry, showed a higher risk of migraine headaches.

- Repetitive negative thinking ameliorates headaches in the short term while exacerbating them in the long term.

Summary

Dr. Yoshinori Sugiura from Hiroshima University’s Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences found a correlation between repetitive negative thinking, such as worry, and headaches among the study’s university student sample (N = 239). People with a tendency toward repetitive negative thinking exhibited an increased risk of migraine by 2.48 times. Detailed analysis concerning repetitive thinking revealed that an earlier stage of repetitive negative thinking is associated with reduced headaches one month later. On the other hand, an exacerbated stage of repetitive negative thinking was associated with severer headaches one month later.

The study was published in the academic journal International Journal of Cognitive Therapy in March 2023.

Background

Migraine and tension-type headaches are common sufferings in daily life. While psychological factors such as anxiety and depression have been associated with headaches, the present study investigated a yet unanswered question: Do repetitive negative thinking worsen headaches even among nonclinical students? Repetitive negative thinking attracts attention as one of the common etiological factors for diverse psychological disorders. If its relation to headaches is revealed, it will open possibilities for psychological therapies.

Also Read: Being too harsh on yourself could lead to OCD and anxiety

Research findings

A questionnaire involving a total of 426 university students was conducted in “two waves,” with repeated measurements about one month apart. This design will tell us whether repetitive negative thinking on the first occasion will predict headaches a month later. Therefore, the direction of influence will be clear. The degree of headache was measured multidimensionally: frequency, severity, and interference with life. In addition, screening questions for migraine status were answered.

1. People with a tendency toward repetitive negative thinking indicated a higher risk of migraine headache

Among people without migraine at first testing, those who scored high on a tendency for repetitive negative thinking were 2.48 times more likely to experience migraine one month later. As self-reported migraine and its clinical diagnosis have already been shown to be in high agreement, it can be said that repetitive negative thinking predicted the onset of migraine headaches.

2. Repetitive negative thinking weakens headaches in the short term while exacerbating them in the long term

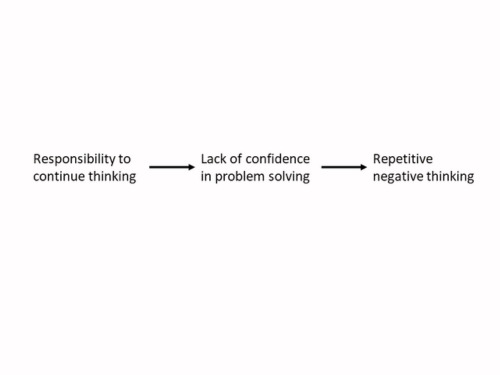

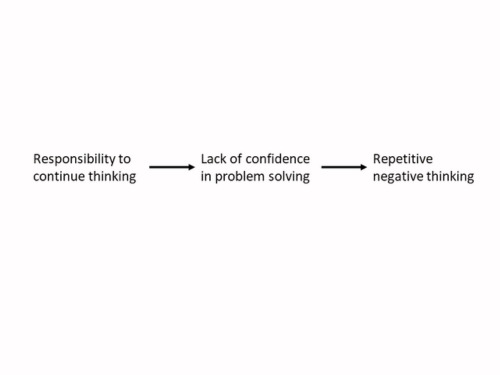

The research team has elucidated the process where repetitive negative thinking becomes more severe and perseverative (Figure 1). When we encounter everyday nuisances, the inflated responsibility to continue thinking makes it difficult to let problems go and avoid dwelling on negative thoughts. As such, responsibility is tied to an inflexible style of thinking, and reaching a solution becomes difficult. A lack of satisfaction in problem-solving further fuels perseverative thinking, leading to full-blown rumination or the repetitive dwelling on negative thoughts.

Figure 1. Process of development of repetitive negative thinking

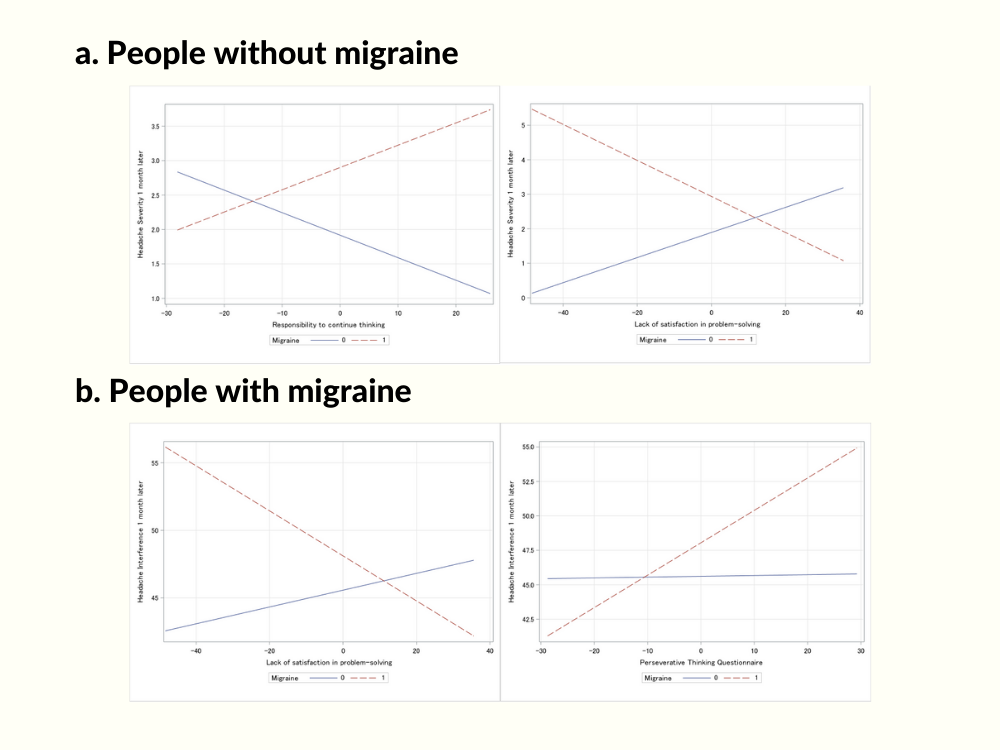

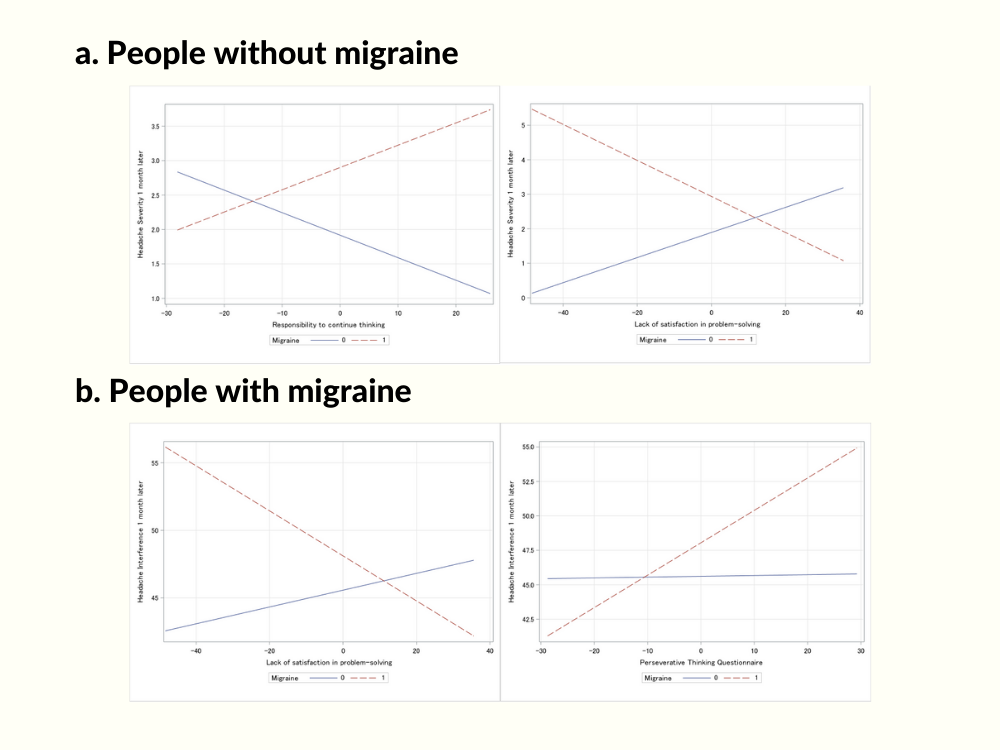

The present research measured three processes in Figure 1 to find differential correlations with headaches one month later. Patterns of correlations also differed across those with and without migraine.

a. People without migraine

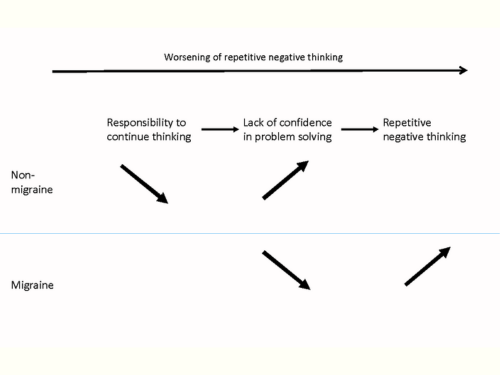

There were wide individual differences in headache severity even among this subsample. This group may be mainly experiencing tension-type headaches. A high responsibility to continue thinking predicted reduced headache severity one month later. On the other hand, a lack of satisfaction in problem-solving led to severer headaches one month later (solid blue line in Figure 2a). Figure 3 integrates these findings with the cognitive process depicted in Figure 1. As the responsibility to continue thinking is located at an earlier stage of repetitive negative thinking, it is still associated with constructive problem-solving and is less pathological. Therefore, repetitive negative thinking at this stage can distract one from headache pain. However, when negative thinking leads to thwarted problem-solving (Lack of satisfaction in problem-solving), it will increase psychological and somatic distress (e.g., muscle tension), thus worsening headache symptoms.

b. People with migraine

Again, considerable individual differences in the severity of headaches were observed in the migraine group. In this group, a lack of satisfaction in problem-solving predicted reduced headache interference a month later. On the other hand, repetitive negative thinking worsened headache interference one month later (broken red lines in Figure 2b). Figure 3’s lower panel shows the critical point where repetitive thinking turns from a reduced to increased headache slide rightward, toward the severer end of the repetitive negative thinking process. As results reported in Section 1 showed, those with migraine have a higher tendency for repetitive negative thinking. Therefore, they may be located on the severer end of the repetitive negative thinking process. While the state of thwarted problem-solving is distressing, there still remains a residue of effort at problem-solving. Therefore, repetitive thinking barely retains its anti-headache function. However, when repetitive thinking ends in full-blown repetitive negative thinking, it exacerbates interference from headaches one month later.

Additional data were obtained from 92 participants, where the questionnaire survey was replicated at a one-week interval. This new data showed repetitive negative thinking reduced headache severity one week later. Repetitive negative thinking can reduce headaches in a shorter period (That said, as the additional sample is small, the latter results are tentative and require replication).

Figure 2. Processes of repetitive negative thinking and headache by migraine status.

a. Among people without migraine, a high responsibility to continue thinking reduced headache severity one month later. A higher lack of satisfaction in problem-solving led to severer headaches one month later (solid blue line).

b. Among people with migraine, lack of satisfaction in problem-solving reduced headache interference one month later. On the other hand, repetitive negative thinking worsened headache interference one month later (broken red lines).

In sum, the present study found that repetitive negative thinking increased the risk of migraine. While repetitive negative thinking reduced headaches at an earlier stage, it worsened them in the longer term. Temporary relief of headaches by repetitive negative thinking may reinforce the latter further, thus leading to the vicious cycle of increased headaches due to the cumulative effect of negative thinking.

Figure 3. Schematic description of how cognitive factors align with increased perseverance being differentially related to headache after one month, according to initial migraine status.

Future directions

Repetitive negative thinking may be a target of psychotherapy for headaches (e.g. Mukai & Sugiura, 2022). Over-reliance on analgesic drugs is known to exacerbate headaches. Therefore, a non-pharmacological alternative is highly recommended. In addition, while temporary, repetitive negative thinking can reduce headaches. Another fruitful approach is to investigate the strategic use of “thinking” to cope with depression. People spend about half of their waking time thinking of something other than what is in front of them. Indeed, repetitive negative thinking is an example of the “wandering mind” phenomenon. Conditions under which mind wandering is adaptive are being elucidated (e.g. Sugiura & Sugiura, 2020). This line of investigation will lead to an easy way to handle headaches.

Media Contact

Inquiries on the study

Associate Professor Yoshinori Sugiura

Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences

E-mail: ysugiura * hiroshima-u.ac.jp

(Note: Please replace * with @)

Inquiries on the story

Hiroshima University Public Relations Office

TEL: 082-424-3701

E-mail: koho * office.hiroshima-u.ac.jp

(Note: Please replace * with @)

Home

Home