Funada, Yoshiyuki. "The Image of the Semu People: Mongols, Chinese, Southerners, and Various Other Peoples under the Mongol Empire (Chinese page)". 西域歷史語言研究集刊. 沈衛榮主編. 科學出版社, 2014, p.199-221, 978-7-03-040378-0.

Associate Professor Yoshiyuki Funada at the Department of History, Graduate School of Letters and School of Letters, is researching the rule of the Mongol Empire and multiethnic and multilingual societies. Specifically, I have examined the rapid expansion of the Mongol Empire and the accompanying large-scale movements of human groups and social changes from various perspectives, including the reorganization and categorization of human groups, the relationships between Mongol rulers and local communities, multilingual documental administration, and language contact in eastern Eurasia.

Yoshiyuki Funada

Graduate School of Letters, Associate Professor

Research Fields: Humanities;History;History of Asia and Africa

In this paper, I challenge the prevailing theory of the “four-class system” of the Yuan dynasty by examining the real image of the Semu people. “Semu people” means “various kinds of people”, and in this instance refers to various people from Inner Asia and areas further west. During the Yuan dynasty period, this term was used to refer to people other than the Mongols, Han people, and Southerners (who were the inhabitants of the north and the south of China proper, respectively).

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the commonly accepted view of this society was the “four-class system of the Yuan dynasty Chinese society”. This view holds that the Mongols regarded the Semu people as partners in the rule of China proper. In contrast, the Han people and the Southerners were considered as lower class; they were discriminated against and oppressed in various aspects.

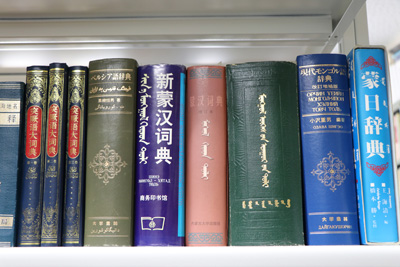

However, terms and concepts referring to the Semu people only appear in historical materials written in the Han language (i.e., Chinese) and not in any non-Han language (e.g. Mongolian or Persian) historical materials. In my research, I found that both the term and the concept of the Semu people were created by the Han people. I also found that the division of people into Mongols, Semu, Han, and Southerners was created by the Han people. This division, therefore, was not shared by the rulers of the Mongol Empire and all the groups under its rule and cannot be considered the foundation of the rule of China proper. I have also concluded that the classification of the Semu people, which had been regarded as a higher class than the Han in previous studies, was merely a product of the administrative system and not a form of discrimination characterized by class or status.

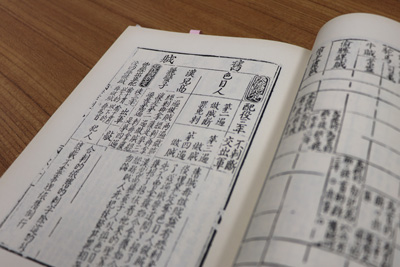

Historical materials about the Semu people

Why, then, was the concept of the Semu people created by the Han people? The answer can be found in the Yuan historical sources. When the Mongolian imperial central government began to implement its full-fledged rule of China proper, it introduced a tax system that originated in Central Asia. Local Han bureaucrats, however, argued that it would be more appropriate to adopt systems native to China proper. The reason behind this argument was to help preserve the customs and systems of the Han people. As a result, the term Semu people appeared in official documents to describe the people outside the framework of the systems that applied to the Han.

Subsequently, the concept of the Semu people took root in China proper. However, at its first appearance, the term “Semu people” was not well-understood by people of that time so the operations of the system required that the scope of the Semu people be clearly defined by the central government.

Based on the analysis of empirical evidence, this paper contradicts the existence of the above mentioned four-class society in the institutions of the Yuan dynasty. As a result of this work, relevant parts of world history textbooks for Japanese high schools have been rewritten.

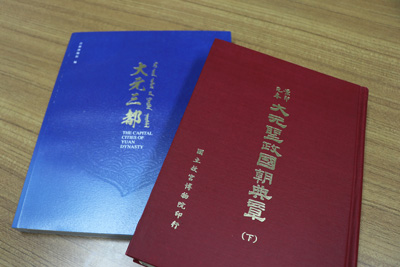

Historical materials that Associate Professor Funada used for his research

Dictionaries of various languages to help read historical materials in foreign languages

Home

Home