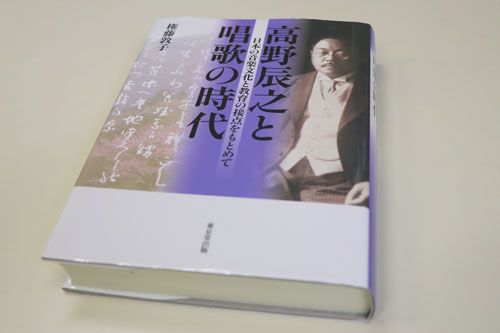

Atsuko Gondo. Takano Tatsuyuki to Shoka no Jidai [Takano Tatsuyuki and history of songs]. Tokyodo Shuppan, 2015, 519p., 9784490209136.

The period from the late 19th century to the 20th century was a turbulent era that saw a push for modernization in Japan. The nation’s traditional folk musical culture also underwent major changes brought about by the state-level policy, and the acceptance of Western music was rapidly advanced in the name of promoting national music (kokugaku) by blending Eastern and Western musical styles.

Atsuko Gondo

Graduate School of Education, Professor

Research Fields: Social sciences, Education, Education on school subjects and activities

In this book, I focus on Tatsuyuki Takano (1876–1947), who not only contributed to the development of national music during an era that saw the establishment of the modern state and school-based education system in Japan but also continued to exert himself for the inheritance and development of Japan’s own culture as a folk heritage. While engaging in the preparation of national textbooks at the Ministry of Education, Takano also devoted himself to the study and preservation of traditional Japanese music as a professor at the Tokyo Academy of Music. Even while toiling in a milieu that would determine the direction of state-level education, language, and music, his enormous achievements and the thoughts incorporated therein confronted an essential question rooted in the context of their own culture: “What should our songs be?”

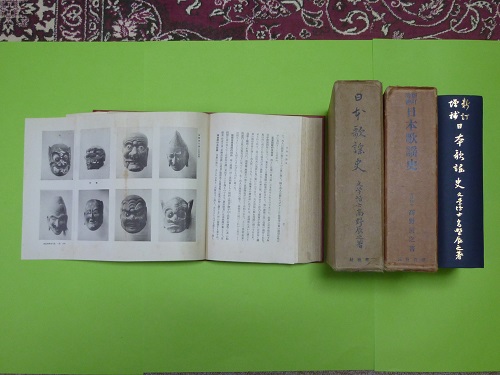

This is an important question that resonates even today. In an era when songs were sung as per the set norms regarding the score, Takano avoided getting tangled up in questions of convention or skill, insisting instead on the importance of everyone freely being able to express their own ideas through song. Further, in his major work Nihon kayō-shi [“A History of Japanese Song”] (1926), Takano surveyed history from the ancient period to the modern, illustrating the cyclical process of Japan’s surprising encounters with new musical cultures from overseas, followed by their imitation, assimilation, and reconciliation. Even while incorporating new extrinsic music cultures, he argued that the fact that music culture is constantly evolving, a constantly changing vitality is more important than the formation of a classical canon, and that during the process of transmission, songs would be unique to the culture.

Hence, even in the contemporary period of ongoing globalization, Takano’s work offers us many insights on reconsidering the potential of songs to be viewed as our own culture.

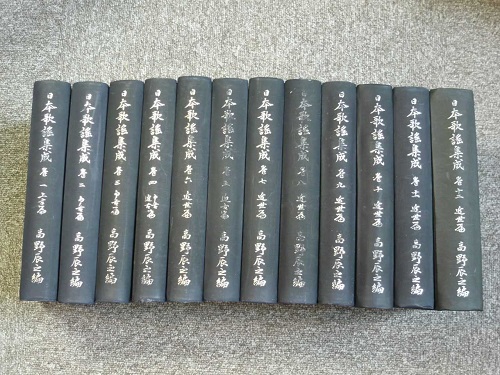

Authored and Compiled books by Tatsuyuki Takano

Home

Home