By Hiroshima University Department of Public Relations

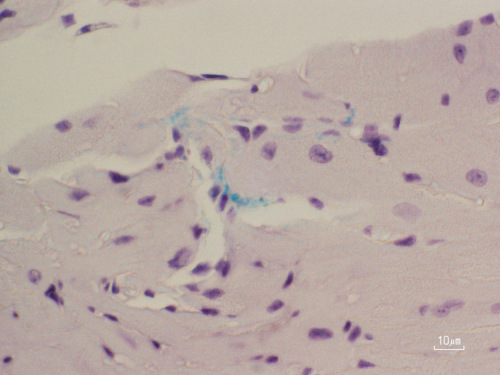

Immunohistochemical staining in mice shows Porphyromonas gingivalis (green) entering cardiac muscle through small blood vessels in the left atrium. (Courtesy of Shunsuke Miyauchi/Hiroshima University)

Tempted to skip the floss? Your heart might thank you if you don’t. A new study from Hiroshima University (HU) finds that the gum disease bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) can slip into the bloodstream and infiltrate the heart. There, it quietly drives scar tissue buildup—known as fibrosis—distorting the heart’s architecture, interfering with electrical signals, and raising the risk of atrial fibrillation (AFib).

Clinicians have long noticed that people with periodontitis, a common form of gum disease, seem more prone to cardiovascular problems. One recent meta-analysis has linked it to a 30% higher risk of developing AFib, a potentially serious heart rhythm disorder that can lead to stroke, heart failure, and other life-threatening complications. Globally, AFib cases nearly doubled in under a decade, rising from 33.5 million in 2010 to roughly 60 million by 2019. Now, scientific curiosity is mounting in how gum disease might be contributing to that surge.

Past research has pointed to inflammation as the likely culprit. When immune cells in the gums rally to fight infection, chemical signals they release can inadvertently seep into the bloodstream, fueling systemic inflammation that may damage organs far from the mouth.

But inflammation isn’t the only threat escaping inflamed gums. Researchers have discovered DNA from harmful oral bacteria in heart muscle, valves, and even fatty arterial plaques. Among them, P. gingivalis has drawn particular scrutiny for its suspected role in a growing list of systemic diseases, including Alzheimer’s, diabetes, and certain cancers. It has previously been detected in the brain, liver, and placenta. But how it manages to take hold in the heart has been unclear. This study, published in Circulation, provides the first clear evidence that P. gingivalis in the gums can worm its way into the left atrium in both animal models and humans, pointing to a potential microbial pathway linking periodontitis to AFib.

Also Read: Gum infection may be a risk factor for heart arrhythmia, researchers find

“The causal relationship between periodontitis and atrial fibrillation is still unknown, but the spread of periodontal bacteria through the bloodstream may connect these conditions,” said study first author Shunsuke Miyauchi, assistant professor at HU’s Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences.

“Among various periodontal bacteria, P. gingivalis is highly pathogenic to periodontitis and some systemic diseases outside the oral cavity. In this study, we have addressed these two key questions: Does P. gingivalis translocate to the left atrium from the periodontitis lesion? And if so, does it induce the progression of atrial fibrosis and AFib?”

Examining the gum disease-AFib link

To simulate how P. gingivalis might escape the mouth and wreak havoc elsewhere, researchers created a mouse model using the bacterium’s aggressive W83 strain. They divided 13-week-old male mice into two groups: one had the strain introduced into the tooth pulp, the other remained uninfected. Each was further split into subgroups and observed for either 12 or 18 weeks to track the cardiovascular risks of prolonged exposure.

Intracardiac stimulation—a diagnostic technique for arrhythmia—revealed no difference in AFib risk between infected and uninfected mice at 12 weeks. But by week 18, tests showed that mice exposed to the bacterium were six times more likely to develop abnormal heart rhythms, with a 30% AFib inducibility rate compared to just 5% in the control group.

To see if their model accurately replicated periodontitis, the researchers examined jaw lesions and found its telltale signs. They detected tooth pulp decay and microabscesses caused by P. gingivalis. But the damage did not stop there. They also spotted the bacterium in the heart’s left atrium, where infected tissue had turned stiff and fibrous. Using loop-mediated isothermal amplification to detect specific genetic signatures, the team confirmed that the P. gingivalis strain they had introduced was present in the heart. In contrast, the uninfected mice had healthy teeth and no trace of the bacterium in heart tissue samples.

Twelve weeks after infection, mice exposed to P. gingivalis already showed more heart scarring than their uninfected counterparts. At 18 weeks, scarring in the infected mice had climbed to 21.9% compared to the likely aging-related 16.3% in the control group, suggesting that P. gingivalis may not just trigger early heart damage, but also speed it up over time.

And this troubling connection was not only seen in mice. In a separate human study, researchers analyzed left atrial tissue from 68 AFib patients who underwent heart surgery. P. gingivalis was found there, too, and in greater amounts in people with severe gum disease.

Master of stealth assault

Past studies have shown that P. gingivalis can invade host cells and evade destruction by autophagosomes, the cellular garbage crew. This ability to hide inside cells suggests a way by which it can slip past immune defenses and trigger just enough inflammation to cause harm without being flushed out. Infected mice showed a spike in galectin-3, a biomarker for fibrosis, and higher expression of Tgfb1, a gene tied to inflammation and scarring.

The findings suggest that brushing, flossing, and regular dental checkups might do more than promote oral hygiene, they could also help protect the heart. Keeping gums healthy could block the gateway for a P. gingivalis invasion.

“P. gingivalis invades the circulatory system via the periodontal lesions and further translocates to the left atrium, where its bacterial load correlates with the clinical severity of periodontitis. Once in the atrium, it exacerbates atrial fibrosis, which results in higher AFib inducibility,” Miyauchi said. “Therefore, periodontal treatment, which can block the gateway of P. gingivalis translocation, may play an important role in AFib prevention and treatment.”

The team is now working to strengthen interdisciplinary collaboration between medical and dental professionals in Hiroshima Prefecture to improve cardiovascular care.

“For the next step, we’re investigating the specific mechanisms by which P. gingivalis affects atrial cardiomyocytes,” Miyauchi said. “We’re also now focusing on establishing a collaborative medical and dental system in Hiroshima Prefecture to treat cardiovascular diseases, including atrial fibrillation. We aim to expand this initiative nationwide in the future.”

Other co-authors in the study include HU School of Dentistry’s Miki Kawada-Matsuo and Hitoshi Komatsuzawa from the Department of Bacteriology, Hisako Furusho, Ayako Nakajima, Pham Trong Phat, Masae Kitagawa, and Mutsumi Miyauchi from the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathobiology, and Kazuhisa Ouhara from the Department of Periodontal Medicine; Hiroshima University Hospital’s Hiromi Nishi and Hiroyuki Kawaguchi from the Department of General Dentistry, Noboru Oda, Takehito Tokuyama, Yousaku Okubo, Sho Okamura, and Yukiko Nakano from the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, and Toru Hiyama from the Division of General Medicine; HU Collaborative Research Laboratory of Oral Inflammation Regulation’s Fumie Shiba; and HU School of Medicine’s Taiichi Takasaki and Shinya Takahashi from the Department of Surgery.

(Research news authored by Mikas Matsuzawa)

Home

Home