Inquiries on the study

Rie Hatakeyama

Postdoctoral Researcher

Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University

E-mail: r-hatake39 * hiroshima-u.ac.jp

(Note: Please replace * with @)

Hiroshi Oue

Assistant Professor

Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences, Hiroshima University

E-mail: hiroshi-o * hiroshima-u.ac.jp

(Note: Please replace * with @)

Inquiries on the story

Hiroshima University Public Relations Office

E-mail: koho * office.hiroshima-u.ac.jp

(Note: Please replace * with @)

Study suggests tooth loss, not low-protein intake, drives memory decline in aging mice, hinting that reduced chewing may influence brain health.

Mice that lost their molars showed significant memory decline despite receiving the same diet as controls, hinting at the impact of reduced chewing on brain health. (Courtesy of Rie Hatakeyama)

Tooth loss doesn’t just make eating harder, it may also make thinking more challenging. A new study from Hiroshima University shows that aging mice missing their molars experience measurable cognitive decline, even when their nutrition remains perfectly intact.

The results are published in the December 2025 issue of Archives of Oral Biology.

“Tooth loss is common in aging populations, yet its direct neurological impact has remained unclear,” said Rie Hatakeyama, postdoctoral researcher at Hiroshima University’s (HU) Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences and first author of the study.

“Our study examines whether tooth loss itself, independent of nutritional deficiency such as a low-protein diet, can cause cognitive decline in male mice.”

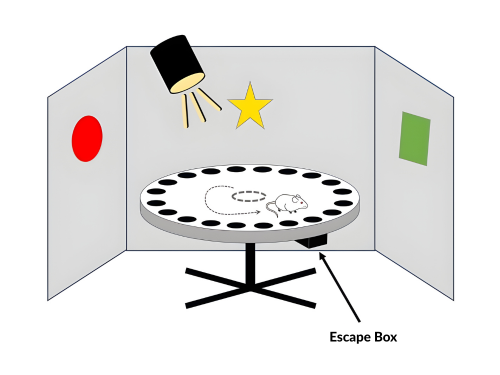

To explore how chewing ability and nutrition jointly influence the brain, the research team used aging-prone male mice and assigned them to one of four conditions: a normal-protein diet with no tooth extraction, a low-protein diet with no extraction, molar extraction with a normal-protein diet, and molar extraction with a low-protein diet. After six months, the mice underwent behavioral tests and detailed analyses of their brain tissue for markers of inflammation, neuronal loss, and cell death–related gene expression.

At 3 months of age, mice underwent either tooth extraction or a sham operation and were assigned to one of four groups: control group with a normal-protein diet, control group with a low-protein diet, tooth loss group with a normal-protein diet, and tooth loss group with a low-protein diet. Behavioral testing and brain analyses were conducted six months later. (Courtesy of Rie Hatakeyama)

Chewing loss, not diet, suggests cognitive decline

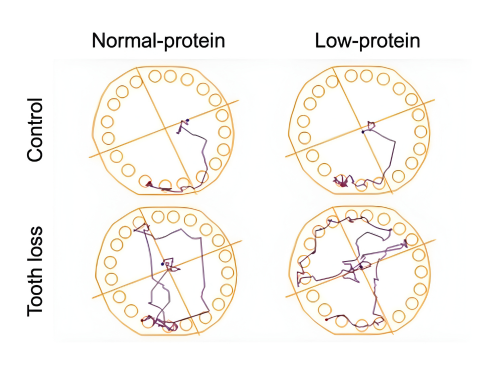

The results were striking: mice that lost their molars showed significant memory decline even though they received the same diet as the control groups.

Experimental tooth loss in SAMP8 mice was associated with cognitive decline and increased neuronal inflammation in the hippocampus, while the effects of a low-protein diet on neuroinflammation were limited. (Courtesy of Rie Hatakeyama)

A movement trajectory sample for each group. (Courtesy of Rie Hatakeyama)

“This suggests that reduced masticatory stimulation, not dietary protein intake, contributes to cognitive deterioration,” Hatakeyama said. “It is surprising that a peripheral event in the mouth can so profoundly affect the central nervous system.”

Brain tissue analysis supported these behavioral findings. The results showed no interaction effect between tooth loss and low-protein diet on the levels of the Bax/Bcl-2 mRNA ratio, a marker representing cell death versus survival. Instead, tooth loss alone significantly increased this ratio, indicating a shift toward pro-apoptotic, or cell death–promoting, activity in the brain. Losing teeth caused inflammation and cell loss in the CA1 and dentate gyrus regions of the hippocampus—areas essential for memory formation and storage.

Meanwhile, the effects of a low-protein diet were limited to the CA3 region, which plays a role in pattern completion. These findings suggest that a reduction in chewing induces pro–cell death pathways in the brain.

This study adds to growing evidence that oral health is deeply connected to brain health, and that protecting one’s chewing ability may be a simple but powerful strategy for preserving cognitive function later in life.

The team planned to further elucidate the neural mechanisms that link mastication to brain function, including potential changes in hippocampal activity, neurotransmitter levels, and neurogenesis.

“Our ultimate goal is to demonstrate, in humans, that maintaining or restoring mastication through prosthodontic treatment can help prevent or delay cognitive decline in the elderly,” Hatakeyama said.

Other members of the research team include corresponding author Hiroshi Oue, Miyuki Yokoi, Eri Ishida, Takayasu Kubo, and Kazuhiro Tsuga of HU's Graduate School of Biomedical and Health Sciences. Yokoi is also affiliated with the Fujita Health University.

The study was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant Nos. 20K10035, 22K17114, and 20K100725.

About the study

Journal: Archives of Oral Biology

Title: Tooth loss induces cognitive decline independent of low-protein diet intake in male mice

Authors: Rie Hatakeyama, Hiroshi Oue, Miyuki Yokoi, Eri Ishida, Takayasu Kubo, Kazuhiro Tsuga

DOI: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2025.106421

Home

Home