By studying the history of sound, we can learn about today’s Japanese: The phonetics of kanji, a former foreign language

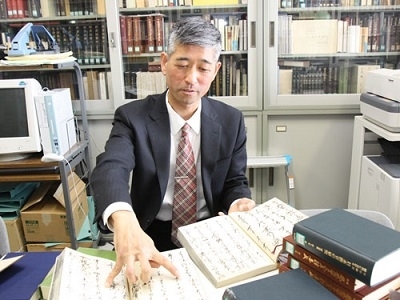

In this edition of Research NOW, we interviewed Professor Isamu Sasaki, Japanese Language and Culture Education, Program in Language and Culture Education, Graduate School of Education.

(2010.February 22nd, Interviewed by Community Collaboration, Information Policy Office, and Public Relations Group)

Profile

“I was born in Sado, Niigata. Because I was raised in a rural area, I had no ‘dreams,’ and simply attended the local high school and college,” says the Professor.

Akira Kaneko, a Niigata University professor (currently at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University: Japanese history research) who Professor Sasaki first studied under, showed him a Shinran glossed “Sanjouwasan” and asked “What do you think the red points mean?” When he looked at the book, there was indeed red around the kanji. Of course he did not understand what they meant, and with this as a trigger, he began to research “the words of Shinran.”

He found something he wanted to do!

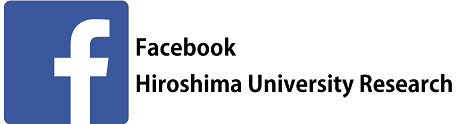

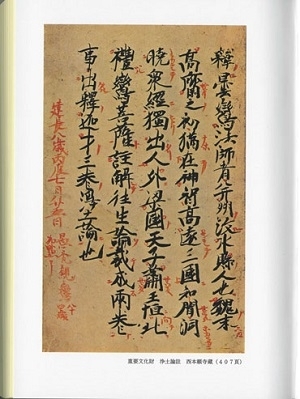

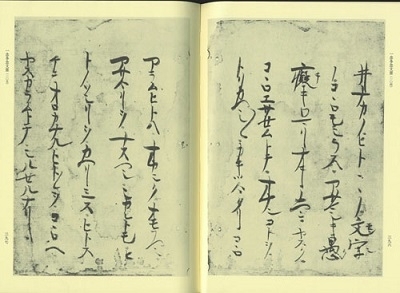

Shinran glossed “Sanjouwasan”

from “Enlarged Shinranshounin Shinsekishuusei” (2005-2007, Hozokan)

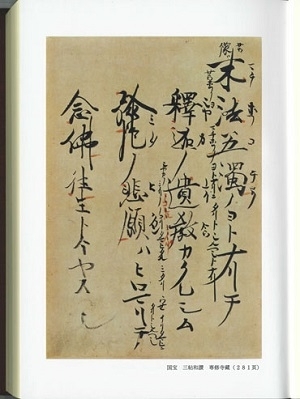

Tone gloss image drawn in the “Sanjouwasan” which is owned by Senjuji.

from “Enlarged Shinranshounin Shinsekishuusei” (2005-2007, Hozokan)

The literary photographs given in this interview article are all from “Enlarged Shinranshounin Shinsekishuusei” (2005-2007, Hozokan).

Kanji that was adapted from China, came along with its sounds.

Professor Sasaki said, “First, let’s talk about kanji. Kanji originally came from China, and are characters that are meant for Chinese. Kanji is known to have a glossed reading and sinoxenic reading. There is the Wu-dynasty reading and Han-dynasty reading for these sounds.” These are the words he used to begin explaining a difficult area of research to an utter amateur like myself.

Already with an expression like “!?” on my face, the professor opened up a dictionary and said, “try looking up the word 『木』 for me.” I wasn’t sure whether I should search for “ki,” or if I should search for “moku.” The Chinese-Japanese character dictionary that was in my grasp had under 『木』, glossed reading “ki”・”ko”, Wu-dynasty reading “moku” and the Han-dynasty reading “boku.” The Wu-dynasty reading came to Japan before the Han-dynasty reading. The combination of the Wu and Han-dynasty readings, mixed with the glossed and sinoxenic readings that make up “kanji,” is what transforms it from a foreign word to a foreign origin word.

“In Japan, you don’t see people who are proficient in English go to a cafe and order a ‘coffee.’ They will pronounce it ‘ko—hee’ as it is recognized as an adopted word in the Japanese language” said Professor Sasaki. Presently, as foreign words continue to get absorbed in the Japanese language, the emphasis on making it easy to speak is what accounts for the change from a Chinese word to a Sino-Japanese word.

More than half of current Japanese is sinoxenic, which means it was originally Chinese. There are also many words that mix the sinoxenic and glossed readings. A very relatable example that the professor used was “Hiroshima Daigaku” (Hiroshima University). “Hiroshima” is the glossed reading of its characters, whereas “daigaku” is the sinoxenic reading. If you read it all as the sinoxenic reading, it would be pronounced “Koutou Daigaku,” which is a completely different word and would not be recognized at all.

By trying to divide things into small pieces, its appearance changed.

The answer to the question, “what do you think the red points mean?” by Professor Kaneko was tone gloss. They were the marks that represent the accents.

While being cautious of kanji tone during his research, he understood that one kanji accent cannot be generalized for all circumstances. That is where professor established his hypothesis that the reading does not change because of the type of document. So he divided the materials into various groups.

The 6 groups are as follows.

Group 1: Materials in which we read Chinese texts with its sound, Sinoxenic reading materials like when reciting the ‘sutra’

Group 2: Materials used in the Chinese text lessons which are read in its glossed reading, and among them, the materials are Classical Chinese texts such as “The Analects of the Confucius” and “Moshi”

Group 3: As well as the above glossed reading of Chinese texts, Buddhist scriptures such as “Dai-Jionji Sanzou Hoshi den” are included

Group 4: Among glossed reading materials of Chinese texts, scriptures such as “Shomonki”, “Honcho-Monzui” were written in Japan

Group 5: Chinese character dictionaries such as “Kujaku-Kyo-ongi”, “Ruiju-Myogishou”

Group 6: Japanese language dictionaries such as “Wamyo-Ruijushou”, “Iroha-Jiruishou”

Comparing the sounds in these six groups, he found that both tone and sound formation were more normative in Group 1 and Group 2, while they were written as more Japanized kanji sounds in Buddhist texts of Group 3, and further Japanized kanji sounds were progressed in the Chinese classics written in Japanese in Group 4. Comparing kanji sounds between Group 5 and Group 6; he found more normative kanji sounds in the kanji dictionaries of Group 5. This result shows that Japanese kanji sounds vary due to the differences of users’ learning level, their purposes for use, and places to use.

Awarded the “Shinmura Izuru Prize!”

Professor culminated his research results in his “Research of the Han-reading of Chinese characters during the Heian and Kamakura eras” materials compilation (2009 Kyuko Shoin). “Selecting a few representative materials from my research, I arranged all the pronunciations of the kanji and compiled them together. I believe this materials compilation can be used for a long time. I wish for many people to use this, and want people to have at least one cumulative source,” said the professor who has expectations for his work to be used in practical applications.

And this thorough experimental study led to him being awarded the Shinmura Izuru Prize in 2009.

This prize, which is awarded to those who provide an important contribution to Japanese philology or linguistics is seen as a pioneer to Japanese language research, as it was organized in 1982 by the Shinmura Izuru Memorial Foundation, which honors the achievements of Shinmura Izuru who compiled the Koujien (Japan’s most authoritative dictionary). However, in 2007 and 2008, there was no leader of this organization, which made for two consecutive years of harsh standards by which to award the prize. Professor Sasaki in 1987, was awarded the prize as a member of the Kamakura Period Language Research Society (Representative at the time: Yoshinori Kobayashi, Department of Literature. Currently Hiroshima University emeritus professor), making this his second time celebrating this brilliant achievement.

An encouraging byproduct

The professor said, “I did not realize it until it was all gathered together, but while arranging the representative materials of the Japanese and Chinese phonemes, I understood that the ratio of tone gloss changed depending on the material groups.” This was received as an unexpected byproduct of his work.

It was understood that the ratio of the tone gloss that comprises the entire phoneme of the material is as high as the normative material group (close to the first group).

Even presently, beginner students of foreign languages note phonetic symbols, accent marks, and word pronunciation accents on the pages they read. However, as they learn the language, the number of phonetic marks on the Japanese alphabet decrease, and begin only inputting accent marks. Advanced students use more accent annotations, and the ratio for use of phonetic symbols on the Japanese alphabet decreases, Professor Sasaki believes.

Wanting to close in on all the literary remains of Shinran!

Professor is currently invested in a new research project. He has an especially strong will to complete this challenge: “There are many different hand-written documents that were left behind by Shinran, and I would like to receive all those documents and clarify the sound of kanji. It would allow me to clearly see the phase contrast of kanji during the Kamakura period. This is what I believe to be my obligation as a Japanese born researcher.”

It appears Professor Sasaki was able to gather Shinran’s materials and had a chance to survey his work. He was moved to the point he felt goose bumps, and felt a renewed sense of determination towards his research.

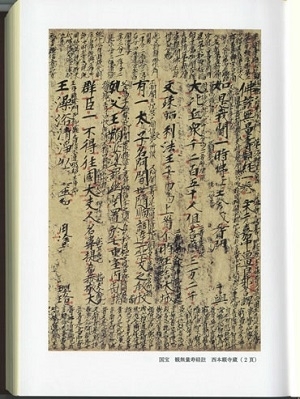

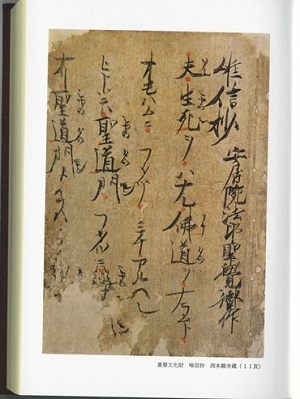

Japanese reading materials “Kanmuryoujukyouchu” contains only a vestige of the detailed tone gloss of the Japanese phonetics.

The “Joudoronchu” Chinese reading and Japanese-style reading of the document has an increased ratio of Japanese pronunciation.

The kanji and katakana mixed Nishihongan-ji collection “Yuishinshou” used kanji that took the shape of Chinese words, carefully adding tone gloss and Japanese syllables.

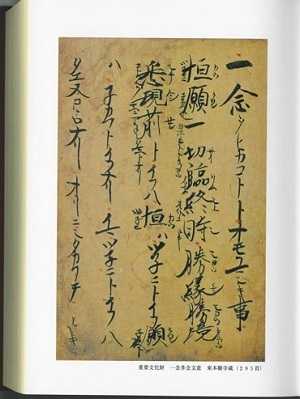

With the publication of the “Ichinen tanen mon-i,” explanations became simpler as a result of the pronunciation indicators next to the kanji.

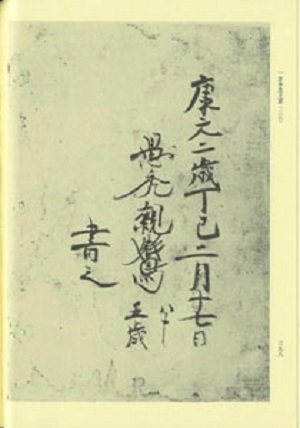

Shinran’s handwritten epilogue of the “Ichinen tanen mon-i.”

At the end of this “Ichinen tanen mon-i,” the following was inserted:

「田舎の人々の文字の心も知らず、浅ましき、愚痴極まりなき故に、易く心得させむとて、同じ事をとりかえし/\書き付けたり。心有らん人は、おかしく思ふべし。嘲りをなすべし。しかれども、人の誹りを省みず、一筋に、愚かなる人々を、心得易からむとて、記せるなり。

康元二歳丁巳二月十七日 愚禿親鸞 八十五歳 書之」

「田舎の人々」(Country people) Readers would assume 「易く心得させむとて」(to be easily understood) that Shinran had decided that the written “Yuishinsho mon-i” and “Ichinen tanen mon-i” did not need tone gloss accents, the professor analyzed. Desperate to make it available for common people to understand this work, that he continued to the age of 85, “I want more people to read this!” says professor Sasaki as it seems like he is channeling Shinran’s spirit.

The determination to have “more and more people read these!” can be seen.

Afterword

While Professor Sasaki was speaking to me in his soft-spoken manner, there was a moment when I felt a powerful conviction in his words. “Research using ancient texts is an extremely interesting discipline to help you understand our past and our present. I work with writings that are always faced with the threat of burning in a fire, and want that to have an impact on our lives today. Having engaged in this research, I feel that this is the obligation of researchers in Japan,” said the Professor. Perhaps I was completely absorbed by his words, but by the end I had been wishing that these resources do not meet the misfortune of being lost in a fire or war, and that we can pass this information on to the next generation. A force to be reckoned with, Saint Shinran! To be able to continue this work until the age of 85, you were no normal being. You must have been in great health to be able to do this work. I envy him... (O)

Home

Home