Developing a Method of Swine Artificial Insemination Using Frozen-Thawed Spermatozoa: How to Create the Next-Generation System of Pig-Breeding, Supporting not only Japan’s but also all of world’s Pig Industry

We talked to Associate Professor Masayuki Shimada, Animal Science Division, Department of Bioresource Science, Graduate School of Biosphere Science.

(July 2nd 2010, Interviewed by the Community Collaboration and Information Policy Office)

The joint research team of Associate Professor Masayuki Shimada and Oita Prefecture Research Guidance Center for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries developed a novel method of artificial insemination for swine using frozen-thawed spermatozoa and published their study results at a press conference on June 24th. This autumn, Oita prefecture will start distributing frozen spermatozoa.

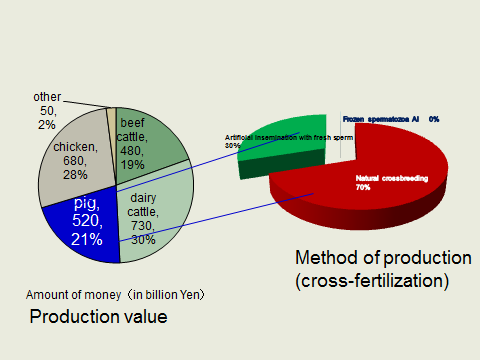

The situation of pig-breeding

In the case of cow-breeding in Japan, artificial insemination with frozen spermatozoa is the dominant technique. Also 30% of pig-breeding is based on artificial insemination with fresh sperm, while 70% is natural crossbreeding. Previously it was very difficult to get satisfactory results with “frozen spermatozoa”, and it hasn’t been officially introduced for artificial insemination.

Domestic swine production (Market share of frozen semen)

The results of insemination have been sporadic. The Oita Prefecture Research Guidance Center for Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries faced this issue. “Although one pig does well, the method failed with another pig. Even with the same pig, there are times of success and failure. What’s the reason? “One of the researchers of this center, Dr. Tetsuji Okazaki, asked Associate Professor Shimada, his senior at university, for help. That was the start of this research project.

Associate Professor Shimada’s special field is molecular biology and endocrinology (hormones). His research objects are human or animal ovaries and ova. Specifically his recent research was on human fertility treatment. “Why doesn’t it work? I’ll try to explain the reason from the point of view of biology and endocrinology!” Associate Professor Shimada and his group worked hard to find the answer. After spending more than five years overcoming various issues, they created a method with satisfactory results.

“Frozen spermatozoa” could support Japan’s future food production system

What is the advantage of “frozen spermatozoa” anyway?

As frozen spermatozoa can be preserved in liquid nitrogen almost indefinitely, the valuable genes of pedigree livestock or brand-name pigs can be maintained even in cases of epidemic like foot-and-mouth disease etc. Furthermore, it won’t be necessary to breed boars as the sperm can be stored in a tank with liquid nitrogen. In addition frozen spermatozoa can be thawed and used immediately when a sow shows estrus status. Therefore, it enables a planned production at low cost and supports the business of the pig farmers.

That means the possibility that the use of frozen spermatozoa and the spreading of this method all over the world including Japan will change the pig industry to a more efficient, safety and stabile industrial system. Associate Professor Shimada called this the “Next Generation Swine Production System.”

Storage tank for frozen spermatozoa (Photo Credit: Image by Oita Prefecture)

Technology, efforts and further development of Associate Professor Shimada’s group

Now we will introduce the method developed by Associate Professor Shimada and his group:

(1) Collection of sperm from the boars

(2) Immediately, removing of the sperm from seminal fluid ….Separation of “sperm” and “seminal plasma” (liquid separation)

(3) Cooling and freezing the sperm separated at step (2) and then keeping under liquid nitrogen

(4) Artificial composition of the seminal plasma separated at step (2)

(5) Thawing of the sperm (3) , mixing with seminal plasma (4) and carrying out artificial insemination

Problem No.1: Preservation of strong sperm

Using frozen spermatozoa, it is necessary to freeze the sperm and thaw it afterwards at normal temperature. To withstand these temperature chances, the sperm must be exposure to stress condition.

However, if collected seminal fluid was kept for more than 30 min before freezing procedure, the sperm recovered from same boar would be died. What is it that weakens the sperm? Associate Professor Shimada tracked down the answer.

In fact, a negative factor in seminal plasma, the liquid part of seminal fluid, acted on sperm directly and decreased the sperm motility. To avoid damage from the negative effects of seminal plasma, it is necessary to collect the sperm as quickly as possible (within 15 minutes!) from the seminal fluid. It is also important to add a substance to neutralize the endotoxin released from bacteria in the seminal plasma.

That is why Associate Professor Shimada separated “sperm” from “seminal plasma” by centrifuge just after collection, and froze only the “sperm”; so he could get spermatozoa of high quality.

But there were still some problems that remained unsolved. After succeeding in freezing strong spermatozoa, it became weak during thawing. Actually, the rise of temperature during thawing changes the intensity of the sperm’s cell membrane, and it takes in a large amount of calcium. Recognizing that, Associate Professor Shimada decided to use a calcium adsorbent to avoid absorption by the sperm.

In this manner, a technology for freezing and thawing strong sperm was born.

Problem No.2: Development of seminal plasma consisting only of essential substances

The group of Associate Professor Shimada encountered a new obstacle: Although it was now possible to get the high motility of frozen-thawed sperm, and the successful fertilization was observed in vivo after artificial insemination, the sows didn’t become pregnant. What’s the reason? It was again Associate Professor Shimata who solved the mystery.

As a matter of fact, the seminal plasma, which was separated from the seminal fluid before freezing, proved to be an absolutely necessary matter to enable the implantation of the fertilized ovum and the growth of the placenta. The function of the seminal plasma is to stop the increase of leucocytes in the uterus. In the case of implantation, the leucocytes attack the fertilized ovum as a “foreign substance” ( “nonself recognition”). The seminal plasma helps suppress this attack and to facilitates a smooth implantation.

What is the substance in the seminal plasma supporting implantation? Associate Professor Shimada said: “To tell the truth, I found it on accident!” And he explained: “The fertilized ovum is recognized as a foreign substance, something like an ‘organic transplantation’ within the uterus. Therefore I studied the mechanism of immunosupressants, used to control rejection in the case of organic transplants. I found out that the substance I was looking for was ‘Cortisol’, a matter I had researched it’s concentration within the seminal plasma.”

In separating the seminal plasma from the seminal fluid, ‘Cortisol’ was also unintentionally removed, so implantation became impossible. Associate Professor Shimada developed an “artificial seminal plasma” containing Cortisol. He mixed it with the sperm, and the fertilized ova implanted in uterus. More than ten piglets were born, a number equal to natural crossbreeding.

Even more efforts to increase the accuracy!

Associate Professor Shimada and his group intend to launch a venture company to produce frozen spermatozoa and to offer it to pig farmers. They plan to get semen from the farmers, freeze it and return it to the client.

“There is an additional challenge. It is necessary to separate the sperm from seminal plasma within 15 minutes, but the farmers can’t do that by themselves. They would have to bring the seminal fluid to a place where separation is possible. During transportation the sperm would weaken. We are still thinking of ways to solve this problem”, said Associate Professor Shimada. Even after the publication of his research results, he is working steadily to put them to practical use.

“A task you dedicate your whole live to!” “Be confident!”

Associate Professor Shimada is always telling his students: “If you are not entirely dedicated to something, you never know what you are really cut out for. During your school days, you should find at least one task you are willing to dedicate your whole live to. This research was such a task. Dr. Okazaki, a joint researcher and junior fellow, worked so hard, that he barely slept. Our success is also a result of his efforts.”

Associate Professor Shimada himself has been holding on to his principles. He said,: “Originally, it was my disposition that I believe only what I can see with my own eyes. I always want to make sure.” When he was a third-year student at university, he felt completely immersed in molecular biology, and “that reinforced my wish to investigate questions related to cells. More than in animals themselves, I was interested in ‘cells’. Because the function of cells is the basis of animal life!”

"When I'm interested in something, I'm ardently-devoted to it.," says Associate Professor Shimada.

He mentioned that also in the case of this research, the reason for success was not focusing on the solid substance of pigs, but on “cells”. “Animals as a solid substance are influenced by physical condition and the environment. But the basis is the function of the cells. Studying the mechanism of cells will provide an answer common to all solid substances.”

“Artificial” insemination’s key to success may be a consequence of returning to nature’s principles.

Document image: by Ms. Inzen, Graduate School of Biosphere Science

Postscript

“Why?” - “For what reason?” These are questions important for Associate Professor Shimada. He also answered me very politely and in a way that was easily understandable. The two hours of the interview passed by like a flash, and I couldn’t stop my astonishment. Hearing the news about foot-and-mouth disease spreading, I realized, that Japan’s meat industry is facing a crisis and that the food on Japanese tables is protected by researchers like Associate Professor Shimada. (M)

Home

Home