(Hiroshima University Public Relations Office)

After the atomic bombing, Hiroshima built memorials that transformed unspeakable grief into a global call for peace. Moved by this legacy, Hiroshima University (HU) historian Dr. John Lee Candelaria turned to Southeast Asia’s war monuments in his new book War Memorialization and Nation-Building in Twentieth-Century Southeast Asia—interrogating what stories they etched in stone, the ones left out, and what that means for peace and justice, as the world prepares to mark 80 years since the nuclear devastation.

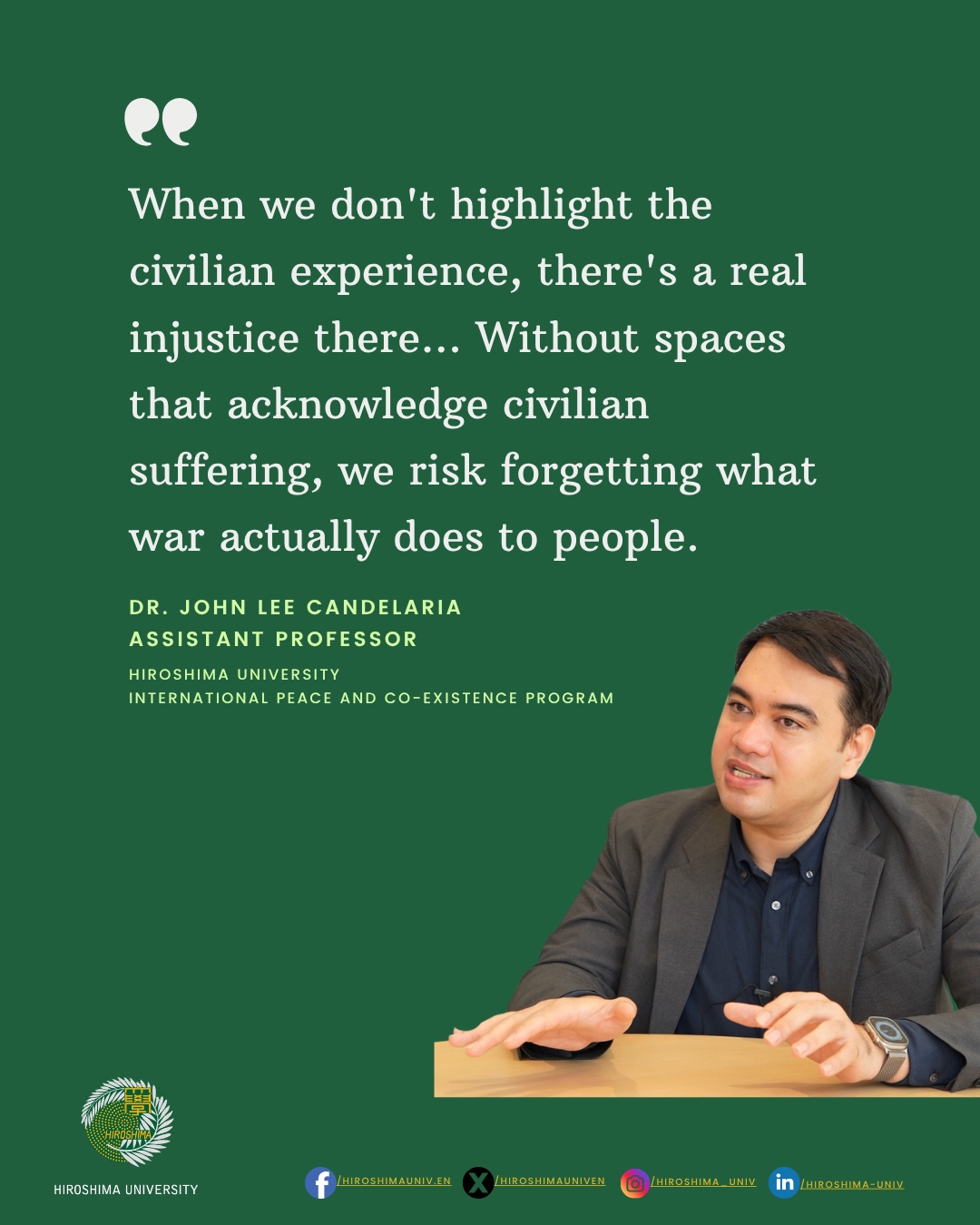

In his book, Dr. Candelaria, an assistant professor at the HU Graduate School of Humanities and Social Sciences’ International Peace and Co-existence Program, investigates war memorials in the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore. We sat down with him to discuss how living in Hiroshima influenced his research, why the stories we tell about war matter, and what his new book reveals about the politics of remembrance.

Q: Your research was shaped by your time in Hiroshima, a city globally recognized for its commitment to peace. How did living and working in Hiroshima inspire your approach to studying war memorials in Southeast Asia?

Being in Hiroshima, I think, is such a privilege as a Filipino, especially because I get to see how Japan is memorializing the Second World War. It's such a consequential conflict, not only for Japan, but for my country as well, the Philippines. I was able to see how, in particular, Hiroshima uses this narrative of war to promote peace. It made me think: What is my country, what is my region, doing to memorialize this war? And what particular aims or agendas are behind that?

Living in Hiroshima has really made me reflect on what these narratives of war and peace mean not just for citizens, but for nation-building in general.

Q: Hiroshima has actively transformed its tragic past into a symbol of peace and reconciliation. How does this contrast with the way war is remembered in Southeast Asia?

I’ve noticed that in Southeast Asia, war is remembered largely for political reasons—but not necessarily in ways that promote peace. Instead, it’s often localized, serving the purpose of nation-building, rather than being used to advance narratives of peace. In fact, in many of the memorials I’ve visited in the region, the focus tends to be on how war united the people—and how, if war were to happen again, the people would come together to fight for the country.

I think that emphasis can overshadow the potential for these memorials to serve as spaces for healing, reconciliation, and the promotion of peace more broadly.

Q: Do you see signs that Southeast Asian countries are drawing inspiration from Hiroshima’s approach to remembrance?

Hiroshima is deeply associated with peace, so I have seen how many Southeast Asians, including Filipinos, especially from Muslim Mindanao (an area of intractable conflict in the Philippines), have come here to learn from Hiroshima’s approach to peacebuilding.

As the 80th anniversary of the end of the war approaches, I think there’s real potential to emphasize how Hiroshima has built a narrative that’s focused on peace. Perhaps countries in Southeast Asia could look to Hiroshima not only as a model for rising from the ashes of war, but also as a guide for how localized war experiences should be remembered.

In that way, I think war memorialization in Southeast Asia could begin to move toward promoting peace, an aspect I find lacking in the region today.

Q: One of the key arguments in your book is that war memorials are not just about remembering the past, but about shaping political narratives. How does this impact their potential to promote healing and justice?

When a nation decides which memories to highlight, and how those memories are visualized through war memorials, it directly shapes societal perceptions of heroism. Going back to the Philippines, historically, we see that presidents, political leaders, and the political elite often draw on soldierly narratives to position themselves as righteous rulers, as people who have the selflessness and capacity to serve the nation.

But war service isn't necessarily an indicator of whether someone will be a good leader, right? Still, there’s something about the values associated with soldiers that resonates strongly with the public. For many among the political elite, it’s a narrative that’s easy to mobilize, especially during elections. There's something noble and enduring about the image of the soldier. It often becomes a kind of surrogate for public service or patriotism.

And that symbolic power carries real political potential, which many leaders have taken advantage of.

We tend to remember the heroism: “My grandfather was a hero.” But we don’t reflect on what happened to those who weren’t fighters, to the ordinary people who bore the brunt of war. If we were able to surface those stories of civilian suffering, I think it would send a powerful message to current and future generations: war should never happen again.

And that’s something Hiroshima does very well. “Just look at what happened to Hiroshima—do we want that to happen again?” That’s the kind of emotional and moral force these memorials can carry. They can help us demand from our leaders real solutions to conflict, ones that don’t lead to war.

Q: Can you provide examples of war memorials in Southeast Asia that effectively represent the experiences of ordinary people?

If there’s one example of a more equitable way of remembering war, especially civilian suffering, it would be the Civilian War Memorial in Singapore. It consists of four tall, identical white columns, each representing a major ethnic group in Singapore: the Chinese, Malays, Indians, and Eurasians. Singapore is a multiethnic society, and this memorial reflects that diversity.

The Chinese community was especially vocal about their suffering during the war, but instead of focusing only on that, Singapore chose to recognize that everyone suffered. So the memorial honors all ethnic groups who experienced loss. I think that’s a really thoughtful way to design a war memorial, one that reflects the diversity of a society, honors different types of suffering, and provides a space where conversations about loss can take place. It’s also a place where families of the victims can come together to grieve. I think we need spaces like that.

I believe the state has a responsibility to honor all experiences—not just those of the so-called heroes, but also the victims. Both are part of the nation's history.

We still have to ask: how can a memorial actively promote peace? That question remains open, but I hope we’ll see more spaces created—not just by the state, but also by communities—that make room for conversations about peace. Because memory-making happens at multiple levels. It’s not only the state that remembers; it’s individuals, families, and local groups too. And their memories matter.

Note: This Q&A has been edited for clarity and length.

Home

Home