Archaeology is an Integrated Science: Determining the Date of the Construction of the 1st Tomb in the Mitsujo Tumulus

In this edition of Research NOW, we interviewed Professor Kiyohide Furuse of Geography/Archaeology/Cultural Heritage Studies in the Humanities Program of the Graduate School of Letters.

(2009 February 18th, Interviewed by the Public Relations Group, Office of the President)

Research Outline

Professor Furuse's primary research is on ancient iron and ironware production in East Asia. He interprets research from the technical history point of view and forwards systematic research of the iron culture across all of East Asia. While pursuing research as a student on iron production and blacksmithing production of ironwares, he happened to become involved in the history of salt as well, which led him to begin research on salt production on the Seto Inland Sea. His research covers a broad range of topics, however, his research is firmly planted in archaeology. Since his employment in the Faculty of Letters as an assistant in 1980, he has been working to advance the field of tumulus culture research through excavation surveys, such as the excavation of Taishaku Ruins.

The Mitsujo Tumulus

The Mitsujo Tumulus, located in the center of Saijo in Higashi-Hiroshima, is the largest keyhole-shaped tomb mound in Hiroshima, and was designated as a national historic site in 1982. The tumulus, which includes a total of 3 graves with the first tomb measuring 92 meters-long, was reconstructed, and over 1800 haniwa figures (unglazed earthen objects) were discovered in the area, leading to its establishment as a tumulus park. In the neighboring Higashi-Hiroshima City Central Library, a Mitsujo Tumulus Guidance Corner was established, where excavated articles are displayed.

Determining the Date of Tumulus Construction from Excavated Ceramic Ware!

From a paste analysis (*2) of a piece of ceramic ware (sueki) (*1) excavated from the Mitsujo tumulus in 1951 by the late Professor Hisakazu Matsuzaki (Archaeology Office, Faculty of Letters, HU), it was discovered that it was a Type TK73, fired by the Suemura Sueki kiln group in the Senboku region of southern Osaka.

During a 1996 survey of a drain in the lower level of the Choshuden Hall, neighboring the Chodoin Hall of the Heijo Palace in Nara (where government affairs and ritual ceremonies took place), a piece of hinoki (Japanese cypress) with the remnants of annual growth rings near the bark was excavated. The Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties examined the hinoki using the tree-ring dating method (*3), and it was determined to have been cut in 412, and at the same time, a TK73 Type ceramic ware, which looked to have been discarded, was also discovered in the same level of the drain.

(*1) A clay pot created from the Kofun Period to the Heian Period. Haji pottery was created through open field burning, which burns at a low temperature, making the firing less intense. Due to this, the pottery has a reddish in color as plenty of oxygen is supplied during the firing process. On the other hand, ceramic ware (sueki) which was fired in climbing kilns built like tunnels into the slope of mountains, are fired at high heats, which cases the oxygen during firing to be cut off, giving them a blue-gray color. Ceramic wares created in the Kofun Period were primarily used in religious ceremonies or as burial accessories.

(*2) Analysis of the components of the clay, which is the primary element of earthenware and ceramics.

(*3) Method of finding the year in which the lumber used to create cultural assets was created by looking at the growth rings from excavated lumber from old shrine/temple pillars, beams, etc. Careful attention is paid to the differences in the width of the rings for each year due to weather conditions such as exposure time to the sun, rainfall amounts, etc. The Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties uses a reading device with an attached microscope to measure the fluctuation in the width of the rings and creates a benchmark pattern from the cumulative data. Currently, they have benchmark patterns for sugi (Japanese cedar) and hinoki from 3,000 years ago.

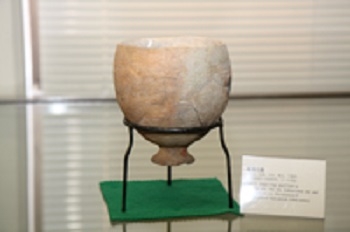

Sueki excavated in 1951 (restored by piecing together fragments found).

At the January 2009 Hiroshima Prefecture Educational Activities Group's Buried Cultural Assests-sponsored symposium “On the Monuments in Hiroshima”, Professor Furuse announced in the keynote address that “I have determined the date of creation for the first tomb of the Mitsujo Tumulus to be approximately 412.”

The professor, who noticed that the type of ceramic ware excavated from the Mitsujo Tumulus in 1951 was consistent with the type of ceramic ware excavated from the Heijo Palace site, comprehensively determined that the ceramic ware was the same type (Type TK73) based on the results of an X-ray Fluorescence Analysis of the amount of chemical elements in the paste of the ceramic ware. From the excavation site, the ceramic ware appears to be ceremonial, and from the size of the tumulus, it can be said that it belonged to someone of great power in the Yamato government who ruled over the entire area.

The Importance of Chance

“Trees that grow in the same region and era develop similar growth ring patterns. Thus, you can create a 1-to-1 correlation between the growth ring patterns of trees, whatever their variety may be. The Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties has benchmark patterns for hinoki and sugi that span over 3,000 years,” says the professor, expressing his admiration for the tenacious research of the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, “From just a single splinter of wood, its age can be identified and the truth comes to light. What is clear from this method is of course, only the age of the tree or shrub itself; it does not necessarily mean that the artifacts found with it are of the same age. However, the answer can be found by using other examination methods in conjunction to determine the age of artifacts,” he says with anticipation.

Professor Furuse's hypothesis, built on the results of many long years of research, and the age of a single splinter of wood, as determined by the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, are what led to the determination of the age of this tumulus. It is a romance born of the chance discovery of the ceramic ware together with the wood fragment. It appears that a new analysis method, aside from the traditional scientific methods of tree ring dating and X-ray Fluorescence Analysis, has been developed and close focus on future archaeological research will no doubt follow.

“Chance is quite important,” says the professor.

Image from “Discovering Eras through Tree Ring Dating”, thesis by Takumi Mitsutani, Director of the Chronology Lab at the Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties, entitled “Creation Theory for Standard Calendar Year Patterns for the Ancient Past.”

Iron is the State

Iron has always been at the center of history. Andrew Carnegie predicted the coming of the Age of Iron, and became King of the Steel Empire and an active man of business through the scale expansion of his iron producing enterprises. Famous for Otto von Bismarck of Germany earned the nickname “The Iron Chancellor” and in his famous “Iron and Blood” speech, said that through iron (guns) and blood (soldiers), Germany will be united, and pressed forward with "iron and blood" policies.

However, in East Asia, iron production technologies came from China (who began iron production around the 9th Century BC) to the Korean Peninsula (iron production began around the 1st century BC) and then to Japan. However, as it was far cheaper to import the iron, Japan chose to import iron manufactured in the south of the Korean Peninsula, rather than to make her own. However, after the anti-Yamato Japan Silla Kingdom in Korea gained control over the Korean Peninsula in the 6-7th century, the south was thrown into confusion and Japan's steady iron supply came to a halt. It was then that Japan for the first time went to observe and learn iron production techniques from the Korean Peninsula and began producing iron in Japan.

Around the 9th century, an improvement in bellows allowed for an enlargement of the kilns, and in the 14-15th century, high-temperature liquid iron production became possible and pig iron production was established. In modern days, Japanese-style iron making has reached the pinnacle of perfection and has come to be known as “Tatara (stepping on bellows) Iron Making”.

There are many phrases in Japanese which reference iron or swords. For example, “tatara wo fumu (to step on the bellows)” which means to stumble, “aizuchi wo utsu (responding to another's story or conversation to show one is listening)” which comes from the blacksmith and his apprentice using hammers (tsu(zu)chi) in rhythm to forge iron (known as “aizuchi”), and many, many more.

Picture scroll (e-maki) depicting ancient Japanese iron-making methods (from “Tatara: Ancient Japanese Iron-Making,” a science reading book published by the JFE 21st Century Foundation)

Iron in the Chugoku Region

Steel was produced in industrial complexes created in the mountains of the Chugoku region, such as Hiroshima and Shimane Prefectures and until traditional production methods were replaced by Western methods, it is said that roughly 90% of all the iron in Japan was produced here. Factories were built in the mountains, as iron sands were collected in mountain streams and to save labor in the transport of fuel such as sawtooth oak and chestnut wood charcoal, needed in large quantities.

Among the highly-pure steel created through the tatara iron making progress, “tama-hagane” or “jewel steel”, an especially exceptional steel, was made famous for its use in the creation of Japanese swords. Currently, the Society for the Preservation of Japanese Swords restored the Yasukuni Tatara Ruins in Okuizumo-cho (formerly Yokota-cho) in Nita-gun, Shimane Prefecture to create the Nitoho Tatara in 1976 and continues to produce materials for Japanese swords and the like.

A sickle made by Professor Furuse with tama-hagane in the forefront.

Tempering by a sword smith (tempering: to beat hot iron into the desired shape).

Salt in the Chugoku Region

From the results of an archeological survey conducted 20 years ago on islands, the ruins of nearly 100 salt manufacturers were discovered in Hiroshima Prefecture. There is a verse in the Manyoshu (The Anthology of 10,000 Leaves) which says to take algae (hondawara) and hang it on a pole, then pour seawater on it and let it dry. You then take the concentrated seawater (brackish water), which is collected in a shallow ditch under the poles, and pour it into earthenware for salt-making. "The brackish water is then boiled, and the salt sticks to the earthenware," says the professor. This method of salt-making earthenware was said to have continued from the middle of Yayoi period to about the middle of the Heian period in the Setouchi region.

In a recent survey by Professor Furuse's research lab members, salt-making earthenware was discovered which appear to be from the Nara Period to the Heian Period in Okawaura and Suyaura in the western coastlands of the Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima. It was written on wooden strips unearthed at Fujiwarakyo in Nara that salt was brought to the capital as tax from Kurahashi-jima (Kurahashi Island) in Kure (nearby to Higashi-Hiroshima). From this, it was learned that this area was quite active in salt-making.

A salt vessel excavated in Hiroshima (Kofun Period).

The Story of the Taishaku Survey Office

The headquarters for the repeated surveys of the ruins in Taishakukyo (canyon), the Taishaku Survey Office (Hiroshima University Tashishakukyo Ruins Survey-Excavation Office) was created in 1977 and has now become a lodging facility for academic staff and students. The survey office was established in 1971 thanks to the efforts of by the late Professor Matsuzaki, and the building was completed in 1977.

Since then, there has been a dramatic improvement in the research environment for academic staff and students, and a great many research results have come out of the office. From the professor's article in the October 14, 2008, issue 116 of the research office magazine, "Iwakage", readers can catch a glimpse of the friendly support of those living in the area, as well as the students who conducted surveys under harsh conditions at the time. While it has currently undergone some renovations, what supports the students as they toil in less than pleasant conditions, working in numbing millimeter and centimeter increments is likely the warmth of that office, which has continued from the day of its creation to the present.

Afterword

Professor Furuse humbly says that "Archaeology is an integrated science." There are human skulls excavated from ruins with finely chiseled features characteristic of those from the Jomon Period (~14,000-400 BC), and there are those with long and thin faces, characteristic of our modern age -- it is all intriguing. From the appearance of the tops of fossilized human skulls, the development process of the jaw can be interpreted. Small and thin skeletal frames indicate that the people of the time were of small stature, however, elliptical-shaped cross-sections of the leg bones indicate that developing muscles were present. Just by speaking to the professor, you'll find that it's not just iron and salt, but in fact much, much more which can be considered "science" when seen from the archaeological point of view.

This interview really made me aware of the depths of the field of archaeology. Even at my level, the relationship between things becomes clearer and as you continue learning, you realize, "Ah! So that's what it was!" I imagine that this is what the joy of learning really is. Actually, there is one more thing. I was allowed to try some of the salt which the professor made in Kamagari (Kure City). I was absolutely thrilled. It makes a great accompaniment for alcohol all on its own, right Professor? (O)

"Go on, try it! Isn't it good?!"

The professor's handmade salt.

Home

Home